“A good tartan is the solution to everything,” writes Trisha Telep in The Mammoth Book of Scottish Romance, a compilation of mythical and magical stories. “It tells you where you are, where you belong, who your friends and family are . . . ”

It’s a heartwarming sentiment. And certainly tartan power, with its special mixture of high style and homeliness, history and contemporary edge, has swept the world. It turns up in Buenos Aires and Hong Kong, on designer catwalks and at punk gigs, on wallpaper and shoes as often as hats and headscarves, and as brand signatures (no one can escape that Burberry plaid) — all a world away from its origins as a homecrafted material from the Scottish Highlands.

Tartan was once best known for its links to the Scottish clan system, in which each family or landlord had its own pattern (or sett, as it’s properly called), usually named for the family or place. In fact, you can still have one of your own if you want to create and formally register it.

But that sense of settled social order and kinship, the epitome of a Scots identity, is really not the whole story. A new exhibition at the V&A Dundee, simply entitled Tartan, uses some 300 items — from the earliest surviving woven scraps to Vivienne Westwood creations, furniture, memorabilia and more — to explore the emotive contradictions and complexities deep in the warp and weft of that unmistakable weave.

Fashion writer Caroline Young, author of Style Tribes, has called tartan “the most politicised of fabrics”. Because for some people, this complex range of endlessly mutating but always recognisable patterns is the emblem of proud Scots independence: in fact, by the mid-18th century the kilt was so much a symbol of Scottish patriotism and rebellion against English oppression that wearing of Highland dress was actually banned by law for a time. Yet other people see it as an emblem of the taming of that very spirit: tartan also became the draping of the establishment, through its links to military power (regimental uniforms) and to aristocratic power and royalty (Queen Victoria’s passion for tartan, in everything from shawls to carpeting, which rapidly spread to the rest of the royal family). Once Victoria visited Scotland for the first time in 1842, she started a tartan craze — and a romanticised version of Scotland itself — that, arguably, has never really ended.

So is tartan a true folk fabric, deeply rooted in the country’s long history, or is it part of a sort of fantasy, “the costume of a fictional construct, a sartorial expression of a Scotland that never was”, as professor of fashion thinking Jonathan Faiers has it? Faiers went as far as to describe it as “fancy dress for off-duty royalty holidaying in the Scottish outposts of a European aristocratic never-never land”.

The V&A’s exhibition gives plenty of food for thought about all this. Tartan’s sartorial reach spread fast: letters to a tartan manufacturer in Bannockburn in the 1820s come from New York, Baltimore, Montreal, Barbados and Rio de Janeiro. Tartan production became mechanised and highly sophisticated — some patterns use up to 180 colour combinations in their weave — and the characteristic colourful grids and checks appeared on silks, cottons, velvet and taffeta, on ribbons, on suiting material and much more. The novels of Walter Scott thrilled the world and established the romantic myth of wild Scottish warriors (tartan-clad, naturally) which has also endured — think of the movie Braveheart. Synthetic dyes allowed for even brighter colours, and as tartan was more than anything a male fabric — kilts were originally men-only — it was perfect for dandies and swells of the 19th century to display their peacock tendencies in waistcoats and trews, even entire suits.

Tartan’s once dangerous and seditious reputation had morphed into a mass-produced, globally consumed textile, and Scotland’s heritage industry had truly begun.

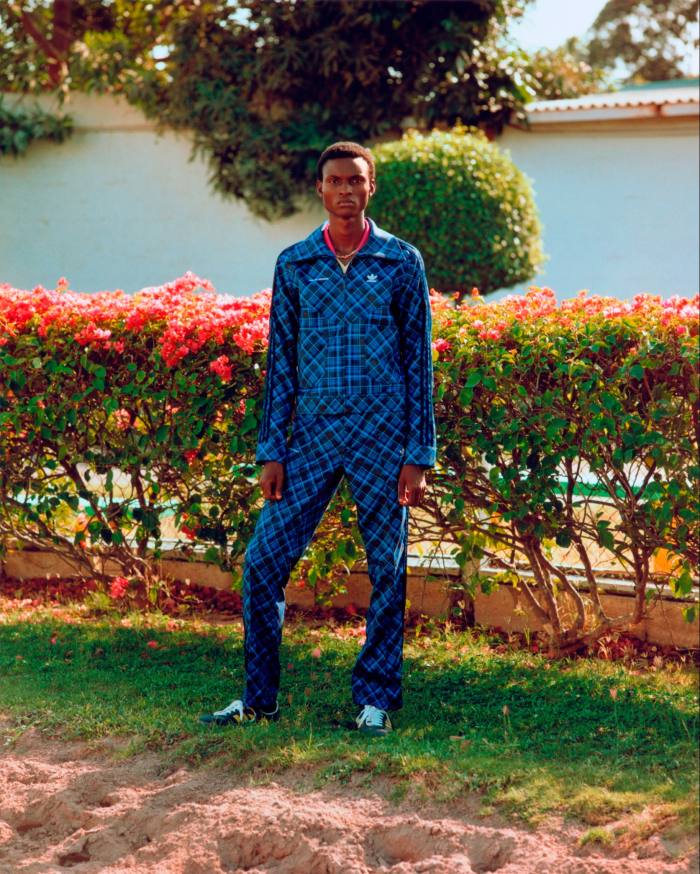

Couturiers began their long love affair with the fabric early in the 20th century — Coco Chanel fell in love with a Scottish Duke in the 1920s; her 1922 silk cape in Gordon tartan is included in the Dundee show. Other high-fashion exhibits include a Dior blouse and kilt ensemble designed by Marc Bohan in 1963-4 and worn by Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor; also from Dior comes Maria Grazia Chiuri’s T-shirt and oversized tartan skirt from 2019. In 2000 Jean Claude de Castelbajac’s Autumn/Winter couture collection went in for tartan overkill (cashmere tartan evening dress, with tartan shawl, gloves, collar and tartan shoes). Alexander McQueen appeared with Sarah Jessica Parker, both rather awkwardly swathed in yards of tartan, at the Met Gala in 2006. And so much more. Moving up to the present day, Nigerian-Scottish designer Olubiyi Thomas has created a brand-new tartan for the V&A.

In more sombre mood, the show explores military tartans with an extract from the 2006 National Theatre of Scotland production of Black Watch by Gregory Burke, and with a kilt worn by a Scottish soldier in the first world war battle of Aubers Ridge in 1915. Though badly wounded he survived to bring his kilt home, still covered in the mud and blood of the Western Front.

Beyond clothing, tartan appears on everything from biscuit tins to ceramics and dressing tables, and cheaper versions of Balmoral’s design excrescences, including tartan carpeting, became standard issue for pubs and bars everywhere. Memorabilia in the V&A’s exhibition includes racing driver Jackie Stewart’s helmet with its Royal Stewart tartan band; weird personal objects include a Hillman Imp car with entire tartan interior and matching picnic basket, and a tartan-clad Xbox controller.

And a pair of homemade trousers from a Bay City Rollers fan, of course. Tartans were adopted by the world of pop in all sorts of ways. New Romantics added frilly sleeves and lace jabots; punk rockers and their fans ripped and shredded the stuff. (Who knows whether its wearers were attacking a symbol of establishment aesthetics, or whether they just liked the colours?)

Tartan turns up everywhere in popular entertainment, art, design, literature and film, in instances too many to mention — though who can forget the tartan-clad Eddie Murphy in Coming to America? More recently, Gordon Napier’s film 1745 shows two escaped Nigerian slaves in the Scottish highlands, rather grandly dressed all in tartan.

There’s an old saying that tartan is never completely in nor out of fashion. But its particular emotional power, with all its mysteries and contradictions, does seem eternal. In 1969 Alan Bean, a crew member of Apollo 12, took a fragment of MacBean tartan with him on that historic mission, and was reputed to have left the piece of fabric on the surface of the moon. The astronaut now denies it — presumably ducking a charge of littering in space — but it would have made a very nice story.

‘Tartan’ is at the V&A Dundee from April 1st to January 14 2024, vam.ac.uk/dundee

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @financialtimesfashion on Instagram

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Fashion News Click Here