Dozens of public school students spend their lunchtime with a guitar-playing Baptist minister, bowing their heads in prayer under a tree by the school playground. English classes read Shakespeare and Steinbeck, avoiding works that might draw them into contemporary controversies. Most parents here consent to corporal punishment for misbehaving children, though the superintendent says he rarely swats kids with the paddle.

This tiny district in west Texas is hardly a hub of liberal indoctrination.

Yet Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, is hoping that fear of a “radical woke agenda” in places like this will help him secure a long-elusive goal: a voucher-style program that would award public stipends of up to $8,000 to parents who switch to homeschooling or private schools.

“Our schools are for education, not indoctrination,” Abbott said at one of many recent rallies he has held around the state. “The solution to all of this is to empower parents to choose the school that’s right for them.”

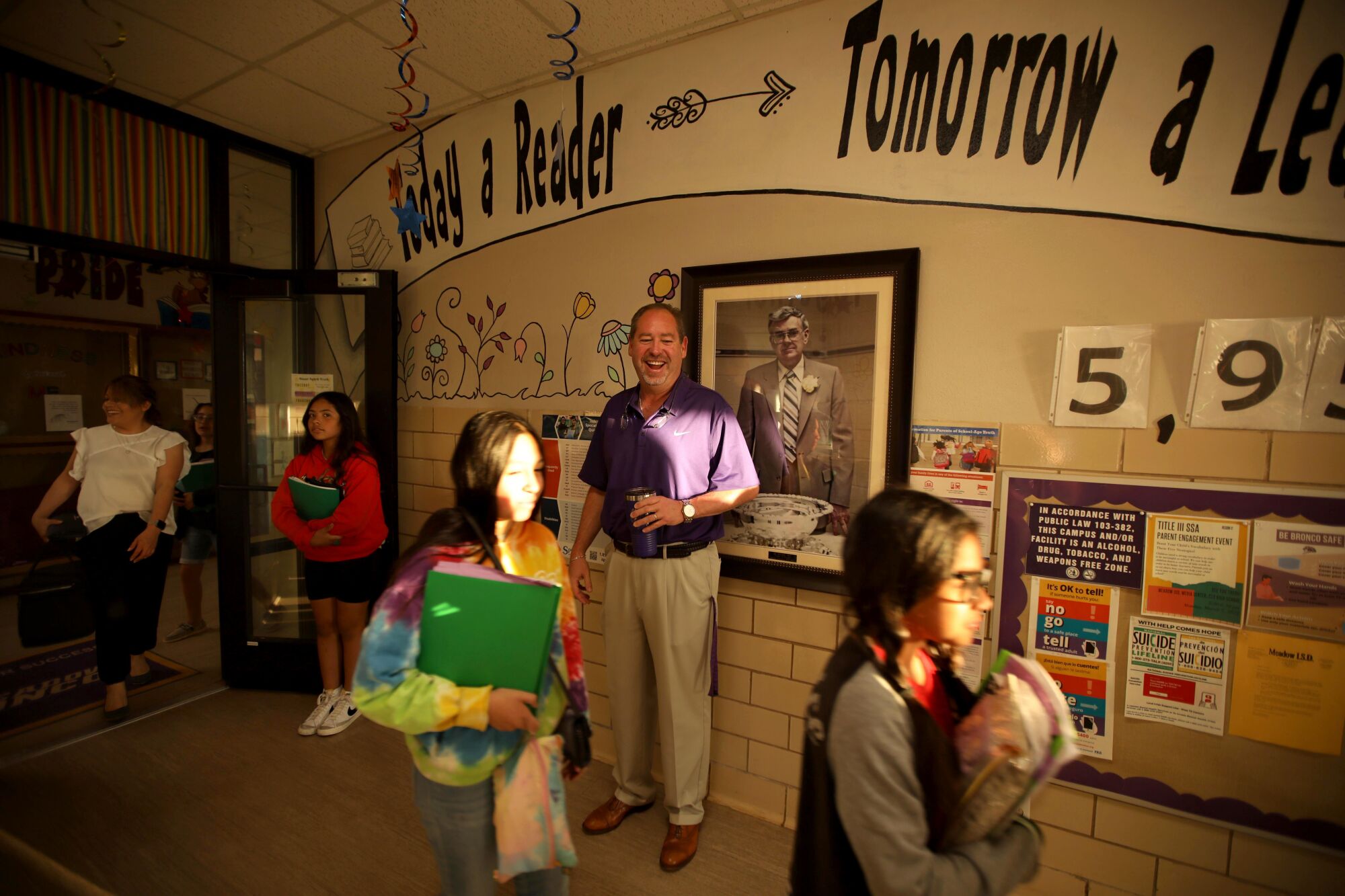

Bric Turner, center, Superintendent of Meadow School, keeps an eye on students who make their way to their first class at the start of the day at Meadow School in Meadow, Texas.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Abbott’s effort will test whether rhetoric about “wokeness” can convince Republicans to abandon even the nation’s most traditional public schools.

So far, many rural Texas conservatives remain unconvinced by the governor’s warnings. Schools here serve as Friday night football venues, leading employers and focal points of community life. Rural superintendents have been able to use their stature to mount intensive lobbying campaigns, persuading lawmakers representing overwhelmingly Republican areas to break with their governor on a bedrock issue.

Abbott is staking political capital on pulling out a victory this legislative session and may yet prevail. Over the past two years, other Republican governors have passed expansive voucher-style bills in states including Arizona, Utah, Iowa, Arkansas and West Virginia. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed an expansive bill in late March, and more than a dozen other states are debating similar measures.

Meadow High School seniors Bryden Smith, left, and Zachery McGee, build a giant black smoker in an agriculture class at the school in Meadow, Texas.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Residents in overwhelmingly Republican places like Meadow worry about the nation’s shifting values. But they don’t see those changes as a problem in their own schools.

“We’re here in a small town for a reason — to kind of protect our kids from that,” said Kenzie Rios, an Abbott voter whose three children attend Meadow Elementary School.

On a Friday at the community cotton gin, farmers and retired farmers gathered for their weekly coffee and doughnut meet-up, which also includes the Baptist pastor and the school superintendent, Bric Turner.

“Meadow schools is kind of being run the same way it was when I was there,” said Ray Gober, an 87-year-old retired farmer who wears the “G” emblem he used to brand on his cattle embroidered into his denim shirt and a large belt buckle with the name of the county, Terry, on his Wranglers.

Ray Gober, 87, hugs Reagan Perez at the weekly gathering for coffee and conversation at Meadow Farmers Co-op, a local cotton gin in Meadow, Texas.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

“You would be ostracized if you were a woke person in this community,” said Robert Henson, an 80-year-old retired cotton farmer and nightly Fox News watcher.

Henson left early to drive an hour out of town to watch his grandson, a pole-vaulter at Meadow, compete in a regional track meet. Henson graduated from Meadow High School in 1960 and his family has attended schools in the district for nearly 100 years, without interruption, since his aunts moved here from Oklahoma in 1926.

The closest private schools are in Lubbock, more than 20 minutes away. But many rural students choose to home school. And like others here, Henson worries a voucher program would eventually pull money from all public schools, even as proponents promise to keep rural school budgets intact for five years.

“If we lose our school, we lose our town,” Henson said. “All we got in this little town is the school and this gin.”

A school bus makes its way through downtown Meadow, Texas. The town’s population is 601 according to the 2020 Census and about two-thirds are Latino. The median income is $64,953 with a poverty rate of 1.19%.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Meadow’s population is 601, according to the 2020 Census, and is about two-thirds Latino. Its elementary and upper schools are housed on a single campus for about 255 students, including roughly one-third from a neighboring small town. More than two-thirds of the students are considered low income; the school provides breakfast and lunch to everyone and to-go bags for those who need dinner. Many of the teachers, administrators and coaches live in school-owned homes, in part because housing is scarce here.

Shop students are building a giant black smoker on the bed of a trailer, which they hope to use next year in regional brisket and ribs cook-offs. Other students are building robots, keeping score of which one moves the most blocks or heavy tuna cans ahead of a competition in Lubbock.

In one classroom, an English teacher uses slang and a wall-sized touchscreen as she breaks down Romeo’s duel with Tybalt.

“That’s your own blood. You marry into a new family,” says America Rios, 33, one of many teachers who graduated from the school. “Guess what? You’ve just killed your girlfriend’s cousin. That’s not good.”

Parents have asked the school librarian to pull a handful of books from the shelves in recent years, but there haven’t been clashes over curriculum or LGBTQ issues, even as it is quietly acknowledged that some kids are gay.

“It’s just more of an acceptance without really talking about it,” Rios said.

Though many of the children and families work in the fields before and after school, all 25 students in this year’s graduating class are expected to go to college or technical school.

**

Principal Jason Atcheson, center, greets students who hang out in the hallway in between classes at Meadow High School, consisting of elementary and upper schools, all housed on a single campus for about 255 students.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Texas, which already allows students to transfer between public school districts or to enroll in charter schools, has lagged behind other conservative states in adopting vouchers.

More than 30 states have some form of voucher or savings account, according to Jason Bedrick, an education research fellow at the conservative Heritage Foundation think tank in Washington. Proponents initially tailored their programs to win bipartisan support, restricting eligibility to low-income families and sometimes using private money. Broader initiatives that used public money and allowed stipends for middle and higher earners were often thwarted by teachers’ unions, which align closely with Democratic lawmakers.

Two statewide ballot initiatives to initiate vouchers in California failed, 70%-30% in 1993 and 71%-29% in 2000. A 2017 poll of California voters found 60% support for vouchers, though a majority of adults rated their local schools an A or a B.

The pandemic supercharged the movement, as shutdowns eroded trust conservative parents had in their public schools while Zoom gave them a window into what was being taught, Bedrick said. Republican politicians responded with a string of “parents’ rights” policies that gave activists more veto power over books and curriculum and added more restrictions on drag shows and gender-affirming care for trans youth.

Joey Harrington, 14, center, holds victorious arms up after winning an exercise during a robotics class at Meadow High School in Meadow, Texas. Students are building robots, keeping score on which one moves the most blocks or heavy tuna cans ahead of a competition in Lubbock.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Bedrick said that stipends give dissatisfied parents not only an “escape hatch,” but also a source of leverage when negotiating with public schools over curriculum and reading lists.

Educators agree, but many see that leverage as a problem, worrying that states and school boards are limiting the teaching of slavery, Jim Crow and other dark chapters of American history and creating an unsafe or unwelcoming environment for gay kids.

Universal voucher programs also tend to benefit high-earners, given that private school tuition is often out of reach for the poor and middle class, even with a stipend.

Second grade students raise their hands to answer a question for teacher Isabella Gonzales-Alaniz, left, during a math class at Meadow School.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

The Texas voucher bill has passed the state Senate, but it faces a tougher climb in the House, which has long blocked passage of similar bills. Rural Republicans, who hear regularly from small-town school superintendents, have been the biggest obstacle to passage in a state where Republicans enjoy large majorities.

Turner, Meadow’s superintendent, has sent emails to local lawmakers, driven to Austin and spoken with parents and community leaders, pointing to a state estimate that the program will draw $1 billion a year by 2028. He doesn’t buy assurances that rural schools will be spared a budget hit.

“I’m gonna take half of whatever cash you got in your wallet… but don’t worry about it because you really won’t feel it.” he said. “You believe in that?”

House members signaled opposition to Abbott’s plan earlier this month, passing a budget that prohibits using public money for private schools. But neither side expects the issue to be resolved until the legislative session ends in late May.

Many parents in Meadow say they know little about the plan’s specifics but trust their local educators.

Lynn Redecop, who homeschools her 14-year-old boy and 12-year-old girl to give them a “godly foundation,” said she loves the community and would be comfortable sending her kids to public school if she had to. Even if she becomes eligible for a stipend, she’s not sure she would accept money from the state unless she understood more about what strings were attached.

Meadow School students play a game of football during a lunch break recess in Meadow, Texas.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Brenda Russell, head of the Central Texas Christian School in Temple, one of several parochial schools where Abbott has held school choice rallies this year, said she cannot accept many more students. But she hopes the bill, which is now open only to students who attended public school the previous year, is eventually expanded to benefit existing private school parents.

In recent years, she has heard more interest from prospective parents worried that kids in younger grades are being taught too much about transgender issues. Her school promises a “biblical worldview.”

**

Rural public schools in Texas can’t quite match that level of religiosity, though some offer a state-approved elective in Bible studies. Teachers, students and parents in Meadow say they don’t hear much about Christianity discussed directly in the classroom. But it’s infused in the culture, with student paintings displaying a cross and biblical verses displayed in the lunchroom along with renderings of athletes and anime characters.

On a recent Thursday, the principal stood up during lunch to announce that the “folks from the Baptist church are over there” and that attendance was voluntary.

Johnathon Jowers, a parent at Meadow school who is also the Calvary Baptist Church’s minister of music, was waiting under a tree by a red picnic table.

Fayth Haile, 18, right, and other Meadow School students, participate in a Youth Bible Study class at the First Baptist Church in Meadow, Texas.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Jowers, wearing a Calvary trucker hat with three crosses over his red ponytail, said the school is very open to “you doing you.” But at its core, it’s “very, very conservative — very not-woke.”

He drew several dozen students to his two 12-minute Bible lessons for middle school and high school students, something the church leads here about twice a month. The day’s lesson, a passage from Joshua, was about fear and doubt. He told the students they are courageous just for being there and standing up for their faith.

“We will never be separated from the love of God,” he said.

He played a song on the guitar before his intern led a prayer seeking courage. Then, he sent the students back to the playground.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Education News Click Here