There has never been much of a dividing line between effective public relations and the spread of religious fervour, and for 25 days in April 2020 the good news of Captain Tom sounded a lot like The Greatest Story Ever Told. The essence of PR is to take the local and the particular and make it universal; marketeers like to talk about the “toothbrush test” in regard to new product lines, the implied question being: “does everyone need one?” In the early lockdown days of the pandemic, twinkly 99-year-old war veteran Tom Moore walking lengths of his garden on a Zimmer frame in support of NHS Charities Together passed that toothbrush test with flying colours: everybody needed him. The trick lay in recognising that fact.

Hannah Ingram-Moore, Captain Tom’s daughter, with a background in retail branding, understood something of that trick. The chain of events that led to her father’s sudden and unlikely global stardom was set out in one of his several hastily ghosted books – the gospel according to Tom – Tomorrow Will Be a Good Day (the £800,000 proceeds from which books the family eventually took to be their own).

You know the story. On the first sunny Sunday of the pandemic, on the very same afternoon that the prime minister had been admitted to hospital with breathing difficulties and the Queen was to appear on television to reassure her isolated nation that “we will meet again”, the Ingram-Moores had a barbecue in the garden of their rectory in the Bedfordshire village of Marston Moretaine. Grandfather Tom was out on his walker trying to build up strength in recovery from a broken hip and a punctured lung after a fall. His grandson, flipping burgers, urged him on; his son-in-law, Colin Ingram-Moore, a chartered accountant, jokingly incentivised him at £1 a lap – £100 if he could make a century of garden lengths before his landmark birthday – and in that banter it seems that Hannah, whose working life involved sales and marketing advice to clients including Fortnum & Mason and Whittard of Chelsea, heard an opportunity.

She made a call to a young freelance PR consultant she had been working with, Daisy Craydon, and suggested she might put the story out to local media outlets in a press release; a JustGiving page was established with a £1,000 target, to raise funds for the charitable arm of the NHS. What followed was – even by the standards of that year of magical thinking – something of a miracle. PR executives who witnessed it stood in awe and wonder. Several commissioned breathless reports, analysing the phenomenon. One came from a company called Carma, “the world’s most experienced media intelligence service provider, expertly helping PR and communications professionals demonstrate the value of their work since 1984” (whether the latter refers to the year or the novel is not clear). That report used Captain Tom’s story as a case study of “one of the greatest demonstrations of the effectiveness of authentic purpose, PR and communication ever achieved”.

The report broke down the events of April into six key parables. One was the power of perfect timing – at the moment Craydon’s press release landed, news editors across the world were in desperate search not only of hopeful human stories, but ones in which “homemade” content looked like a virtue. Another lesson was the imminent prospect of a happy ending. In a landscape of open-ended uncertainty – no vaccine, no cure, rising case numbers – here was a rare tale that came with a built-in crescendo and climax: Captain Tom was 100 at the end of the month (just eight days before the 75th anniversary of VE Day, with which his story shared such resonance). Carma’s graphs show the spread of a different kind of virus from the familiar ones of that period: 898,000 mentions of Captain Tom across the media in 232 territories and more than one and a half million donations to the JustGiving page from 63 countries, with £38m handed over to NHS Charities Together. “A humble press release,” the report marvelled “had changed everything.”

The report canvassed comment from industry leaders about the elements of classic narrative that made Captain Tom’s walk so persuasive: “A hero embarking on a perilous mission to save the less fortunate – a plot line that has resonated among readers for millennia.” Catherine Arrow, executive director of PR Knowledge Hub, summed it up in these terms: “Captain Tom is not just the hero’s journey incarnate. It’s the hero’s journey continued and extended to superhero. He has already endured and now, with great tenacity, he has risen once again.” Anne-Marie Lacey, MD of Filament PR, expanded on that idea. With his experience as a soldier in the Burma campaign – another great national crisis – Captain Tom was able to single-handedly “plug the gap for human reassurance. It’s the classic ‘R’ of the Drip model,” she argued. “Remind and reassure.” (The full acronym generally signifies “differentiate, reinforce, inform and persuade”, though some proponents of those dark arts swear by the rival merits of Aida – “awareness, interest, desire and action”.)

There were certain other serendipitous elements in favour of the story’s unprecedented momentum. One was the fact that on the Friday after the barbecue, the news was picked up first by BBC Breakfast, in an interview in which Captain Tom not only produced the perfect piece of wisdom for the moment – “tomorrow will be a good day” – but announced that his favourite morning presenter was his interviewer, Naga Munchetty. No doubt that sounded too much like fighting talk to the occupant of the rival morning sofa on ITV, Piers Morgan. The following Tuesday, Morgan stole a march on his BBC rivals; he staked £10,000 of his own money on Captain Tom, live on air, and used his 8.7m Twitter following to seed the idea of a knighthood for the captain #AriseSirTom. Nearly £8m was donated to the cause two days later when Captain Tom completed his 100 laps, and donations peaked again on his 100th birthday a fortnight later with the surreal flypast of a second world war Hurricane and Spitfire over the garden in Marston Moretaine, his elevation to the honorary rank of colonel, the confirmation of a knighthood from the Queen, and a No 1 record, You’ll Never Walk Alone, with Michael Ball.

In the meantime, another of Carma’s parables of the perfect narrative had come to pass. While Captain Tom walked, multiple strands and nuggets of “bite-size content” linking to his efforts were generated daily across all social media platforms. Inspired by Captain Tom’s example, others started to walk. There was three-year-old Daisy Briggs, told she would need to use a wheelchair after she was born with spina bifida, who raised thousands of pounds walking 25 metres daily wearing a different colour of the rainbow. Ruth Saunders, aged 104, in Berkshire, completed her own marathon of laps. “Tom, I’ve done it!” Meanwhile, a postmaster in Marston Moretaine, Bill Chandi, committed to work round the clock to deal with the cards and letters of support that flooded in to the family, 160,000 in a week. The Ingram-Moores, having been isolated, were now besieged. Nick Knowles of DIY SOS was seconded to build a fence to keep out paparazzi and reporters who were squeezing through a hedge to catch a glimpse of Tom. And everyone with an opinion found an angle in the story. A Telegraph leader argued that the Great Walk cemented a spirit of intergenerational solidarity: “At a time when some younger celebrities are carping about the isolation or boredom, Captain Moore sets a no-nonsense tone to emulate.” Other commentators gratefully accepted the gift of the contrast between Tom’s great sense of duty to the frontline NHS staff and the hapless government scrambling to squander billions on PPE procurement.

Looking back on all this now, was a different kind of ending to Captain Tom’s story always inevitable? Was it a near certainty that sooner or later another law of PR would kick in, a version of that tabloid and social media truism that, eventually, no good deed ever goes unpunished? It is hard to pinpoint exactly when that different ending started to become a probability – the one that concludes with the current ongoing statutory inquiry from the Charity Commission into the conduct of the Captain Tom Foundation and the enforced demolition of a garden building created in his name – but that other captain who became prominent at that time, Captain Hindsight, might argue for 18 May 2020. That was the date, two weeks after the hero’s birthday, on which the Ingram-Moore family first applied to trademark Captain Tom’s name.

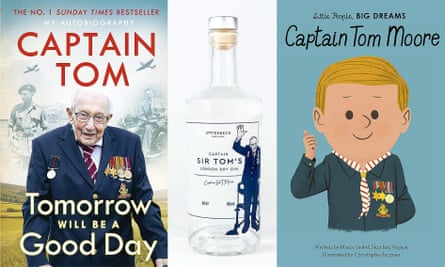

You could see exactly why they needed to do this. As in any cultish phenomenon, there were people on the fringes of Captain Tom-love who demanded relics and material association with him. At a time when the entire economy had been paused, one of the few growth industries was in Captain Tom memorabilia. There were novelty Captain Tom masks with eyeholes, there was a line in Captain Tom duvets, and belts and blazers and numerous styles of Captain Tom T-shirts and collectible handpainted Captain Tom figurines. On the Redbubble website, a “Brighter days are coming” pillow depicting Tom with his war medals was priced at £46 and a bottom-hugging miniskirt sporting an image of the captain with his walker was available for £28. The family, seeking to protect Captain Tom’s newly acquired IP, set up a commercial business, Club Nook Ltd (named after the home in which Tom had grown up), alongside the charitable foundation. Through this enterprise they licensed Captain Tom gin from a distiller in his native Yorkshire, and negotiated a film deal to tell the epic story of the 25 days in April, with the writers and producers of that summer’s feelgood movie Fisherman’s Friends, about the Cornish trawlermen who topped the charts. And then there was a three-book contract with Penguin Random House with designs on the Christmas bestseller list.

You weren’t quite allowed to voice it at the time – because the idea of Captain Tom had become so closely associated with that wave of national sentiment that took in the isolation and loss of beloved grandparents during the pandemic – but an insistent question arose: might all this not be a bit too much? Could any family really bear this weight of adulation afforded to their likable elderly relative? The book, Tomorrow Will Be a Good Day, when it came out, dramatised that feeling. Captain Tom’s ghost writer, Wendy Holden, and his publisher, cleverly framed the detail of his life story against the march of world events: the flu pandemic he was born into, the road to war, the moon landing. His homespun wisdom was set alongside chapter headings featuring Churchill and Gandhi. For all the bravery and determination of his four years of active service during the war, you were left to ponder whether his long and successful career as a salesman and executive in the building supplies industry, the progress of his two marriages, his retirement move to the Costa del Sol, quite warranted that billing. (In another book, part of the Little People, Big Dreams series for children, Captain Tom’s three-week tour of his garden was set alongside the lives of Charles Darwin, Florence Nightingale and Nelson Mandela.)

Tabloid newspapers have long traded on the lucrative idea that any hero worth a banner headline requires a contrasting villain to emphasise their virtue. If the cast at hand does not support that division, then it is manufactured – for every William there must be a Harry, for every Kate a Meghan. It was pretty clear, even from the beginning of the telling of Captain Tom’s story, that his daughter, Hannah, who facilitated his interviews and acted as his spokesperson, might be a confected candidate for that role.

In the family’s confessional interview in October with Piers Morgan, in which they confronted the accusations that they had betrayed Captain Tom’s legacy by blurring the lines between the foundation and their business interests, including accepting an £18,000 appearance fee at an charitable awards event, Hannah Ingram-Moore identified that sentiment from the outset. “With all the love and global admiration,” she said, “there was always an underbelly of hate…”

“What did that underbelly of hate look like?” Morgan asked.

It started on Twitter, Ingram-Moore said. “The deep shock that people would say ‘that bitch should die’, ‘she should be jailed for harming the elderly’, ‘bet she’s got a cattle prod forcing her father around the garden’, ‘hope they all die of Covid’, and it went on and on.”

By the end of 2020, that anonymous sentiment had bubbled up into the mainstream. In December of that year the family accepted the invitation of the tourist board of Barbados to holiday there over Christmas – an ambition on Tom’s bucket list. A month after they returned, Tom was hospitalised with pneumonia and he died after contracting Covid on 2 February. Questions were asked about the wisdom of that luxury Caribbean holiday – though the express philosophy of Captain Tom, who travelled to the Himalayas alone in his 90s, had been to ignore the restrictions of age and live for the moment. Even so, the creeping idea of the family as freeloaders trading on the great man’s reputation was beginning to be established. Sensing that shift in sympathy perhaps should have signalled to the family a natural end of the story – a recognition that what had been a fabulous moment didn’t have to be a managed legacy.

In the absence of that recognition, the family seems to have blundered into their assigned caricature as not being worthy of Captain Tom’s idealised example. In her interview with Morgan, Hannah insisted that her father had always been clear that the profits from his book sales and other “personal projects” should benefit the family directly. Reading between the lines of his book, you can well imagine that to be true. Captain Tom’s impulse to public service expressed itself in ways that David Cameron might have been nostalgic for when he conjured his idea of the “big society” – as a young company executive, Tom Moore had joined the local round table to “give something back”, he organised annual regimental dinners for his wartime pals, and became chair of his local Young Conservatives. Alongside that, though, family always came first. But then how to explain the preface to his book, in which he wrote: “Astonishingly at my age with the offer to write this memoir I have also been given the chance to raise even more money for the charitable foundation now established in my name…”

The sudden unfathomable scale of the events that the Ingram-Moores had set in motion in April 2020 always threatened these kinds of contradictions. Another of Tom’s late-life ambitions had, apparently, been to build a resistance pool in the garden to improve his strength. Somehow, after his death, that germ of an idea evolved first into an L-shaped spa room approved by Bedfordshire council from a planning application that made liberal use of the imprimatur of the “Captain Tom Foundation”, without any kind of approval from the charity’s trustees. The eventual £200,000 building, for which the family applied for retrospective planning permission in 2022, was a much larger C-shaped structure built significantly closer to neighbouring gardens. One of those neighbours spoke for many in saying: “It feels as if they thought that their goodwill gave them cover to do whatever they wanted.” The weird global enormity of the story appeared to have gone to their heads. The evidence for that belief – the infamous indoor spa – gave that part of the public hungry to confirm its worst suspicions about Hannah Ingram-Moore the precise mundane detail it needed. The PR campaign that magnified a local act of fortitude to epic proportion returned to earth.

One perfect tale of middle England – the old soldier returning to service in the shires in our hour of need – has, as a result, morphed into another more familiar narrative, a classic parish scandal of the building of a “windowless monstrosity” that blocks the view of the local church spire. The tabloids could hardly believe their fortune. Drone photographs of the site were splashed. Neighbours were wound up to produce headlines: “Give me a sledgehammer and I’ll knock the place down myself,” said one woman whose garden overlooked “the most controversial building in Britain”. The Bedfordshire council’s planning team, in ordering the demolition of the Captain Tom memorial building, ruled that the C-shaped annexe had been transformed from something commemorating Sir Tom’s record-breaking achievements to “not a high-quality development appropriate for this setting”.

One result of those events is that the feelgood film of Captain Tom’s month of miracles is now on hold. The Charity Commission has yet to report into the conduct of the Captain Tom Foundation, but even in advance of its findings, the foundation has stopped taking donations and will discontinue operations.

If the original story arc provided a manual for successful PR, the reversal of fortunes may well prompt some urgent case studies in how not to manage a reputation. I don’t imagine there is an acronym for it, but one age-old lesson seems to apply: if you do decide to build a spa pool in memory of your recently sainted father, perhaps don’t go to court to argue it is partly “targeted at helping local elderly people struggling with loneliness”. Just stop digging.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Covid-19 News Click Here