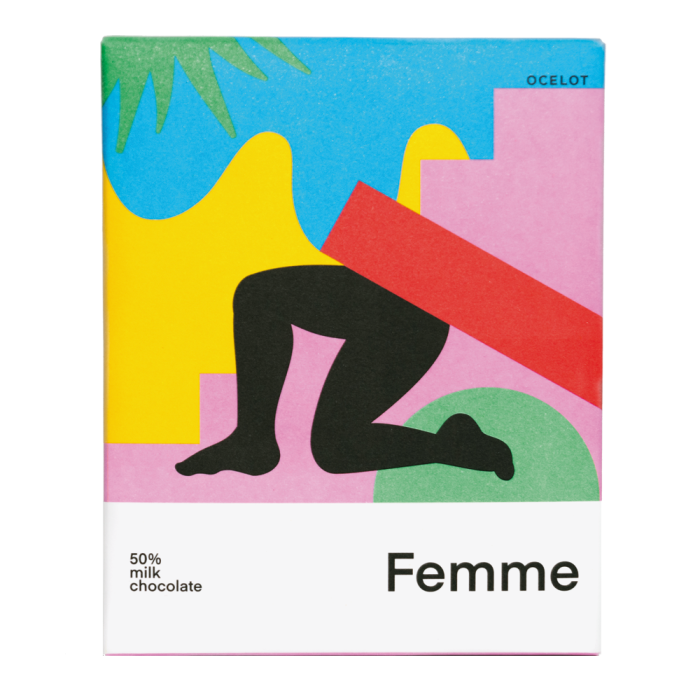

Scan the shelves in your favourite food halls and grocers and you’ll see there’s change afoot in the world of chocolate making. Technicolor wrappers on bars by indie brands boast credentials that sound like a golden ticket to guilt-free indulgence. Ocelot, from Edinburgh, works with the world’s first female cocoa co-operative in Eastern Congo. Tony’s Chocolonely wants to eradicate slave labour. Happi donates one per cent of sales to mental health and environmental organisations. Then there’s HiP – an oat milk bar that declares itself “low-carbon” and “plastic-free” – and Love Cocoa, which has a “one bar = one tree” pledge. It currently plants 50,000 mangroves a month via NGOs.

First came farm-to-table; now it’s bean-to-bar. “It’s a way of standing out on the shelf,” says Ben Greensmith, manager of the UK and Ireland for Tony’s Chocolonely, the 17-year old Dutch disrupter brand that was introduced to the UK market three years ago. With its artisanal notes and colourful, cartoonish packaging, it seems every inch the trendy label. Its most popular global flavour is milk, caramel and sea salt (from £1.35), which comes in a bright-orange wrapper. Tony’s was established to pay farmers fairly and change the cocoa industry from the inside out. This manifesto is reflected in the bars’ “uneven” form. “People find it annoying that the bar can’t be evenly shared, but the cocoa industry is unequal,” says Greensmith. “That’s the point.”

Of course, it’s not the first time the chocolate industry has explored more socially conscious ways of doing business. Fairtrade was introduced in 1992 with an aim to pay cocoa farmers fairly: today, that amounts to an additional $240 per tonne. “Fairtrade is a good start,” says Greensmith. “But it’s traded as ‘mass balance’, sold from giant piles of cocoa that arrive from countless farms. It offers buyers less traceability, visibility or access to direct supply chains. “What it means is someone, somewhere, traded that amount of cocoa fairly,” he says. In other words, he’d like the industry to go further.

Tony’s pays Ghanaian farmers an extra $330 on top of the Fairtrade levy. From 2019 to 2021, it sold 46 million bars worldwide. “We’re not paying them crazy money,” says Greensmith. “It’s just a living income to get them out of poverty and stop using their kids on farms.” Education is key to break the cycle: The East Congo co-operative that supplies Ocelot gives the women access to childcare and adult education, while Zora, launched in February, trades one bar for one girl’s school day in Ghana: its bars, which include pecan and cherry ($11.86), have already funded 400 students. Founder Fatima-Zohra Hakam thinks “it’s important to go the extra mile.”

Chocolate has a complicated history. Its introduction to Europe is tied up with Spanish colonialism. Drunk as cocoa by the Mayans 4,000 years ago in ancient Mesoamerica, it was revered as a bean of the gods and traded as currency by the Aztecs; Hernán Cortés brought it back to Spain in 1528. Slowly, it spread through aristocratic courts: in 1847, Fry’s – a British family-run grocer – turned it into solid bars. Cadbury and Rowntree followed, and chocolate as we know it was born.

In recent decades, it’s been sold as a cheap, mass-produced snack. Some 70 per cent of the world’s cocoa is grown in West Africa alone, but almost all of it is exported. Middlemen and global food conglomerates reap the billion-dollar profits. But it wasn’t always this way. The earliest British makers “were Quakers and philanthropists,” says James Cadbury, the 36-year-old founder of HiP Chocolate and Love Cocoa, and scion of the chocolate dynasty (Kraft took over Cadbury’s in 2010 and the family is no longer associated with its original business). At Bournville, near Birmingham, his great great great grandfather John built clean, affordable housing for workers and offered a then-unheard-of five-day working week. “I wanted to put the heart back into chocolate and create something my ancestors would be proud of,” he says. His Love Cocoa tablets (£4.50), seasoned with rose and pistachio, gin & tonic and avocado among other innovative flavours, are handmade in the UK.

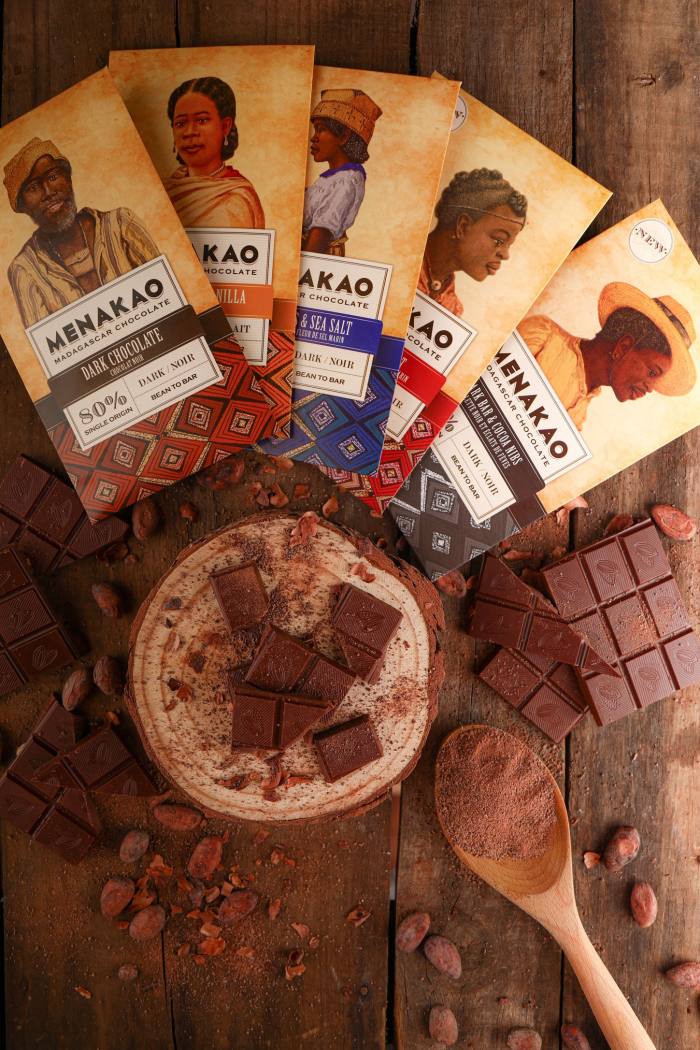

Customers today put their money where their mouth is. Most buyers of HiP are millennials, according to Cadbury. “People care a lot more about what they’re consuming and where they’re spending their money,” says Zora’s Hakam; she’s on the hunt for a chocolate factory in the African continent, to create more jobs and keep profits within the country. Menakao, from Madagascar, is one of the only chocolatiers in the world to make it where it sources the beans. The brand has created 40 jobs and supports 100 more: its packaging features paintings of Madagascan people, visually connecting the global chocolate guzzler with the grower.

This is chocolate 2.0; big-name brands need to adapt. “Chocolate isn’t good for you, but it shouldn’t have to be bad for other people or the planet as well,” says Greensmith. So the next time you crave that delicious cocoa hit, why not scan the shelves and indulge with a bar that’s comforting and conscious – and kinder to the planet. Tastes sweet, indeed.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Food and Drinks News Click Here