First the good news: Indian films are doing tremendously well at festivals abroad. Awards and accolades are rolling in. We’re telling new stories about ourselves, digging deeper, spotlighting the many Indias that mainstream movies never show. You don’t have to scroll too far to find an independent film among the blockbusters and international content on a streaming network today.

The last two years have particularly changed the game. As cinemas shut in the pandemic, films large and small made it to streaming networks, allowing us to watch, at leisure, the kind of movies we never did before, and develop an appetite for it.

Meenakshi Shedde, India and South Asia Delegate to the Berlin Film Festival, Golden Globe voter, and independent curator, says it’s nothing short of a revolution. “In our 120-year history of cinema, we actually have films from regions all over India on the same platform, with subtitles,” she says. “A lot of critics thought Bollywood was the be-all and end-all of cinema. Now, they’re shrieking, ‘OMG, did you watch that Malayalam film?’ But regional films have been around for 100 years. They have woken up to it only now.” Ditto with OTT and audiences.

We’re also worrying less about labels. Rahul Desai, film critic for Film Companion believes that the boundaries between independent cinema, mid-level cinema, and mainstream cinema have blurred in the last decade. “Previously, you could use these labels because of the films’ budgets, or they’d had festival runs, or because they were self-financed,” he says. “Streaming has sort of democratised the game.”

Still, the number of good indie films actually reaching Indian viewers remains tragically low. “India is a graveyard of good cinema,” Shedde says. Many indies often don’t play in theatres. Streaming networks pick up a mere handful of the films out there.

The struggle is universal, but exacerbated in India, says Shedde. There are just too many films vying for our attention. “In 2019 alone, India had produced 2,446 feature films; Hollywood made only 700,” she says. So when 10 films release in cinemas every week, indie films tend to get swallowed up. Streaming catalogues are similarly crowded.

It’s why independent filmmakers still prefer going the festival route. It’s where the interested viewers are.

“Some filmmakers are accused of making films for festivals,” says director Chaitanya Tamhane, who made the 2014 film Court, which was India’s official submission for the 88th Academy Awards. “But the fact is, we take the audience that we get. There aren’t enough people in India watching the films I’m making. But people in the rest of the world are curious. Why would I not tap into that?”

Should a film do well at festivals, it offers a boost, a level of recognition that opens the doors to wider distribution. Film producer and publicist Mauli Singh says that festival darlings such as Court, Titli, Village Rockstars, Tumbbad did enjoy limited theatrical runs in India in the last decade. But the pandemic has shuttered some festivals, so films struggle to get showcased. “Streaming platforms have also started snubbing indies. It’s getting tough.”

The way out, says Shedde is to radically build demand. “Our film industry and film schools are geared towards creating good films – the supply side. None regularly teach criticism and curating, which will create appreciation of good cinema and stimulate the demand.”

Access matters too. Cinema halls must showcase indie films from around the world, Tamhane says. “Independent film will survive despite the struggles. It boils down to the spirit of filmmaking itself, which comes from the urge to express yourself, to tell stories from the world you belong to.”

Take a look at how India’s independent filmmakers are fighting the odds to stay true to the stories they want to tell.

.

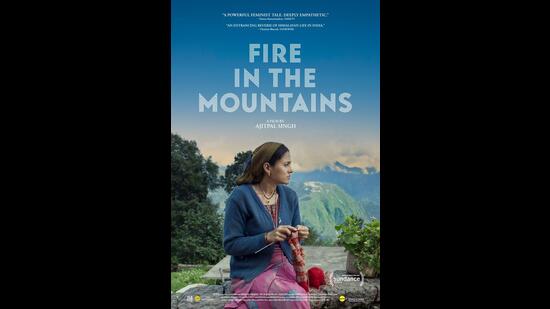

How to move a mountain: Ajitpal Singh

Ajitpal Singh’s debut feature, Fire In The Mountains, was the only Indian film in the world competition category at the Sundance Festival in 2021. He was understandably ecstatic. “You then want to see how it is being received and recognised, which usually begins with big publications writing reviews,” he says. “Then comes the most important part: When will people actually get to see the film? That is usually the most heartbreaking aspect of being an independent filmmaker.”

Fire In The Mountains is the tale of a mother struggling to save money to build a road in a mountainous Himalayan village so she can take her wheelchair-bound son to physiotherapy. Her husband, who believes that a shamanic ritual is the solution, stands in her way. Singh’s story stems from his own life. He lost a cousin to an illness, because her husband refused to take her to the hospital, convinced she was possessed by a ghost.

He’s confident that people will like his film. “But how do I show it to them?,” he asks. The film won Best Indie at the 12th Indian Film Festival of Melbourne, has had glowing reviews in the New York Times and a limited theatrical release this year. But the golden ticket – getting on a streaming network – has been a struggle. “We make films for people beyond the festival screening halls,” Singh says. “Winning is just an extra reward. The intention is always to take your story to people.”

Most streaming platforms, he says, tend to show films that have already been released in cinemas. Or films that turn a profit and don’t demand much thought from viewers. “No one considers or gives the audience the option of variety,” he says. The same platforms have changed the way films are perceived. No film can see itself as purely commercial or fully independent as it was when the parallel cinema movement emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. “But I want my films to reach those whose thoughts haven’t yet been challenged,” Singh says. “That’s when my work is truly done.”

.

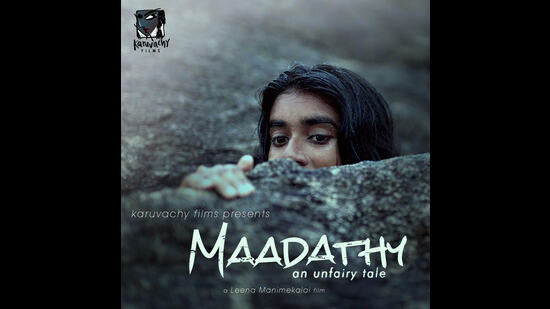

A spotlight on the ‘unseeables’: Leena Manimekalai

Leena Manimekalai believes that in India, cinema is trade, not art. To be an independent filmmaker then, is a curse. “I am living a curse,” she says. But she wouldn’t have it any other way. “I exist from one film to another. I die small deaths in between.”

For nearly two decades, her films have stoked controversies. Her first work, the Tamil short film Mathamma (2002) is a short documentary she made when she was 21. It looked at the sacrifice of female offspring among the Arundhatiyar community in Mangattucheri village near Chennai. “The Arundhathiyar women travelled with it and spoke on stage,” says Manimekalai. “One of the Mathammas even fought elections as Panchayat Counsellor.” (It was some fringe groups that created noise around the film because it exposed gender exploitation.)

Maadathy, An Unfairy Tale (2019), is her 15th film and is made as narrative feature. It centres on the oppressed caste, the Puthirai Vannars or “unseeables” and is the coming-of-age tale of an adolescent Dalit girl, Yosana. It premiered at Busan International Film Festival 2019 and was released on Neestream in 2021. It’s currently streaming on Mubi.

More recently, Manimekalai tweeted a poster of her recent documentary on the Goddess Kaali, which caused nine FIRs to be filed against her. The poster was condemned for its portrayal of a goddess smoking and holding up a pride flag.

“I am just navigating my own detours and finding little joys of sharing my films,” she says. “I have travelled to more than five hundred villages on my own across India and screened films to communities who don’t even have the luxury of electricity, with a battery driven projector,” she says. “Indie films have always found their way to audiences.”

Filmmakers, on the other hand, have to struggle to stay visible, “to be heard, to express freely and not be censored, to speak truth to power, to refuse to be destroyed”. They’ll find a way. “There will always be someone filming the end of the world, seeing the sinking world through the lens without a release date in hand.”

.

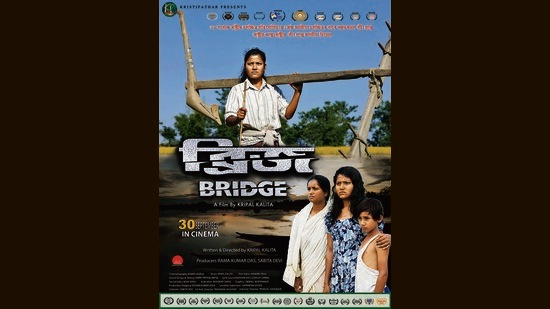

Battling the tide in Assam: Kripal Kalita

The bridge in Kripal Kalita’s Bridge is conspicuous by its absence. It’s been wrecked by the Assam floods, and it’s changed life for those who live along a tributary of the Brahmaputra. So when a TV reporter from Guwahati asks the protagonist, Jonaki (Shiva Rani Kalita) why a bride arrives at her wedding in the daytime, she points out that there’s no bridge to cross the river. “How will the groom travel at night?” Jonaki’s brother Bapukon (Partha Pratim Bora), takes off his trousers and carries them on his head, along with his books, to cross the river on foot just to get to school every day. A woman in labour has to cross the river on a makeshift raft to deliver her baby.

Kalita’s film is a story about overcoming avoidable adversity. It makes for uncomfortable viewing. It won the Jury Special Mention at the 51st International Film Festival of India in Goa earlier this year. Shiva Rani Kalita picked up the Best Actress award at the Ottawa Indian Film Festival, Canada in 2021. It was adjudged Best Film at the Thrissur International Film Festival and at the Golden Jury International Film Festival Mumbai in 2020.

Kalita made the film to highlight how Assam’s annual floods, which get only a cursory mention in the national media, affect daily life in its villages. “The floods have almost stalled development in the nearby villages, houses built only a year ago come crumbling down the next, bridges are broken, medical facilities are pushed further from our reach,” he says. “Nobody wants to show this side of Assam. Everybody wants to highlight development.” The son of a farmer, Kalita crafted his script from his own experiences, from tales he had heard over the years and from newspaper reports. He also filmed on location, depicting Assam’s six seasons, casting locals who were only briefly trained before they made their acting debuts.

He’s given it his all, even his savings. “I had to get this film out,” he says. “If not now, then when?”

Kalita hopes the festival wins mean that Bridge will be picked up by a local streaming platform. “It’s why I made this film: to draw the attention of the rest of the country to the agony of the people in the interiors of the green valley and their tenacity in the face of it all.”

.

A labour of love, stuck in limbo: Chhatrapal Ninawe

For some filmmakers, making a film represents only half the battle – there are also corporate and political forces to contend with. Chhatrapal Ninawe, 41, was thrilled when Jio Studios agreed to co-produce Ghaath, his debut Marathi feature, alongside Drishyam Films in the year 2019.

But 20 months later, just as the film was to premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2021, the studio sent the festival a legal notice blocking its screening. They didn’t even contact Ninawe. It only emerged later that they had an internal dispute with Drishyam Films.

It left the filmmaker confused and disappointed. He expressed his feelings in a post that was widely shared across social media. “I was severely depressed and I could not even afford therapy,” it read. “My career is at stake. Films are said to be the babies of filmmakers. How can I keep my sanity when my baby is being murdered?”

He was met with an outpouring of support from movie critics, filmmakers, and journalists. It also prompted the Berlin festival to invite him back in 2023, this time to screen Ghaath in the Panorama section, the same section it was originally invited for. Buoyed by this encouragement, Ninawe has been looking for a producer to buy out the studio’s rights so it can be finally screened. “So far the studio has been cooperative,” he says.

Ghaath is set in the Naxalite regions of Maharashtra. It follows an undercover left-wing radical looking for the police officer who killed his brother. Set in Naxal territory, it offers a close look at the life of rebels such as the one played by Milind Shinde (above). Even a decade ago he says, he might have not been able to make a film like this, let alone find support for an indie film online.

“I always wanted to make a film in the jungle, about the tribal people because it’s close to my background,” says Ninawe who comes from Nagpur and belongs to a sub-group of the Halba tribe, an indigenous people from Central India. “I had lost faith in people and the system, but it slowly began to grow back. Today, the knowledge that I will find a solution gives me hope. Independent filmmakers tell personal stories that studios might never understand or support. But original, rooted stories will find their way to the people in some form or the other.”

.

The end of the road: Don Palathara

Right from his first film Shavam (The Corpse, 2015) Don Palathara, 36, has been pushing against what it means to be a filmmaker in India. He shot Shavam in black-and-white, on a budget of ₹7 lakh, with a cast of 40 new and inexperienced actors.

The film ended up having a rustic, real feel that is rare, even in independent cinema. It takes a satirical look at the death of Thomas Ittikora, a young Syrian-Christian man. The funeral preparations spotlight the seemingly empty rituals. One mourner asks a visiting expat to find his daughter a job abroad. Others sneak a quick drink in the backyard. There are whispers that the mistress might be present.

Shavam won the Best Foreign Film Award at the Barni International Festival, Moscow in 2016 and toured other international festivals after. It was released on Netflix in 2017.

“It was not as easy as it sounds,” says Kerala-born Palathara, who gave up a career in IT to make independent films. “Shavam was made in 2015, but was unknown to most people until it was picked by Netflix in 2017.” He says it would be naive to expect commercial success for films that differ in form and content from the mainstream. “While it is always nice to get support from outside, I don’t believe it is the responsibility of governments or any external agency to promote or interfere in the process of independent filmmakers or any artists who hold up the independent spirit,” he says.

Palathara has directed four other films since, sometimes crowdfunding to complete them. Public recognition, he says, has only come with the last two: Everything is Cinema (2021) premiered at the International Film Festival Rotterdam last year. Santhoshathinte Onnam Rahasyam (Joyful Mystery, 2021) was released in the United States and is currently streaming on Mubi.

“It’s not easy to survive unless you get recognised,” Palathara admits. Visibility remains one of the greatest barriers for independent films. Streaming platforms are more open to indie titles. But he acknowledges that indie cinema has niche appeal. “The audience for these kinds of films may be small , but I am optimistic that if I manage to produce consistently over the period of a decade or so, I will be able to establish my brand.”

.

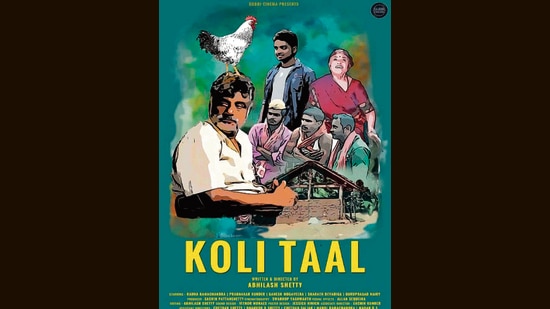

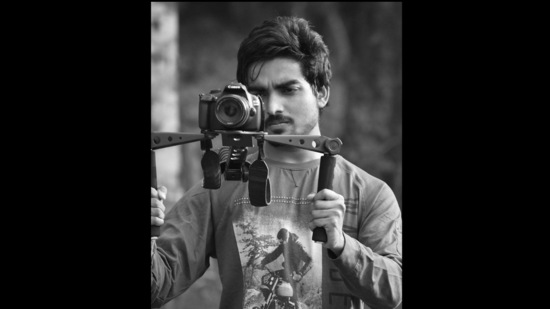

Inspiration in the backyard: Abhilash Shetty

Abhilash Shetty shot his debut feature, Koli Taal (2021) in 15 days, in his grandmother’s backyard in Sagara, Karnataka. It premiered at the New York Indian Film Festival in 2021 and has since been shown at the Indian Film Festival Stuttgart, Germany, the Indian Film Festival of Melbourne and the Jio MAMI 22nd Mumbai Film Festival. This year, it also had a limited theatrical release in multiplexes across Bengaluru, Mangaluru, Mysuru, Udupi, and Shivamogga.

“My understanding of independent filmmaking is to have the freedom to tell a good story and find like-minded collaborators,” says Shetty, 28. In his case, this means staying true to what you know. His 84-minute film follows an elderly couple, preparing for a visit from their grandson from New Delhi. Their lives are upended when a rooster, intended for a chicken curry for the occasion, goes missing.

It’s a story that Shetty has borrowed from his life – he recalls rare visits home from boarding school when a rooster would be kept aside to make koli taal for him. The film, then, depicts village life with a natural flourish. Shetty plays the grandson. Villagers use ingenious hacks to boost the area’s poor cellphone reception. Labourers believe in lucky charms. Much of the minor cast are local first-timers. “Even the mannerisms of actors were picked up from my family members,” he says. “I was merely replicating from memory.”

Shetty quit his accounting job in 2017 to pursue filmmaking. He made three short films soon after, which have been screened at over 30 film festivals since.

Koli Taal, Shetty says, allowed him to depict the specific culture and traditions of a village in the Western Ghats, “something we don’t often see in films”.

For an indie filmmaker, the first film is easy to make, Shetty says. The second and third are progressively more difficult. “Finding a producer becomes difficult because you can’t use the same crew for a different story,” he says. “You have to learn to scale, work with a bigger budget.”

He’s figuring some of that out. Shetty’s second film, also set in the Western Ghats, is in pre-production. He’s not giving up on local flavour. “We need more movies from different parts of India, Indian slice-of-life tales that have never been told but only lived,” he says. “How much song and dance and fluff can people watch after all?”

.

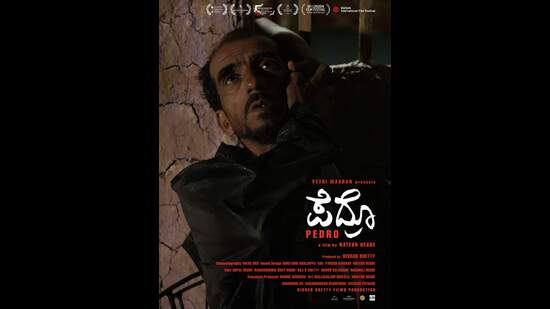

Divided by a boar: Natesh Hegde

Natesh Hegde’s debut film, Pedro (2021) has its world premiere in the New Currents section of the Busan International Film Festival and BFI London film festival; in 2019 it also received the Prasad Lab DI at the National Film Development Corporation’s Film Bazaar.

The story opens with an idyllic picture of rural life — lush trees, heavy rains, comforting monotony. You only realise how volatile village life can be when an estate’s security guard, Pedro, looking out for a rampaging boar, ends up shooting the wrong animal. Simmering communal tensions erupt. Pedro is driven out of the village for his mistake, and forced to live in the forest, where he finds work repairing power lines, never quite forgiven by the community.

Hedge’s story feels authentic because it draws literally from family and home. It’s filmed in his village, Kottalli in the Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka. His electrician father, Gopal Hegde, plays the lead. Several other cast members are relatives and acquaintances. He’s seen exploitation, exclusion and prejudice play out first-hand.

“Communalism is deeply embedded in our society, but any mention of it on screen irks people,” he says. “For this to stop, we must first change society; cinema will follow.”

He says that stories like his – hyperlocal experiences that somehow depict a whole nation – are being told from across India. “If you watch the films of Saeed Akhtar Mirza, you’ll find the same social themes,” He says. “They’re in G Aravindan’s film design, in Mani Kaul and Kumar Sahni’s films. It’s a long-standing tradition that the younger generation is simply carrying on.”

The platform is now larger, the storytellers more confident. But some challenges persist. “Many good scripts never find producers, and if a movie hasn’t shown at a significant film festival, the audience or producers can’t determine whether it’s good,” he says. “Finding distributors and pitching to online video platforms are also challenges, but there is joy in creating a movie you believe in.”

.

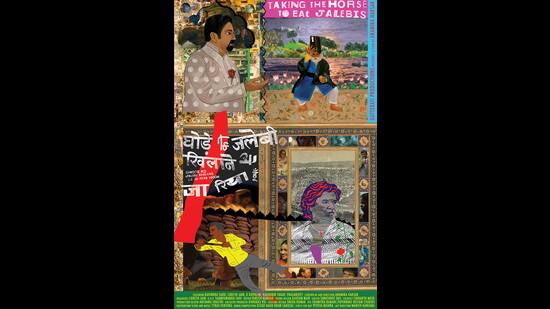

Fears, joys and hopes from capital streets: Anamika Haksar

Theatre director Anamika Haksar’s first feature film, Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon, took over seven years to make. It uses dreamscapes to showcase the hopes of the people who live and work on Old Delhi’s streets – a pickpocket, a sweetshop vendor, a labourer-activist, a conductor of heritage walks.

For the film, Haksar’s team, including Lokesh Jain (who plays the guide in the film), Sarita Sahi, and Chhavi Jain conducted interviews with about 70 people including pickpockets, vendors, loaders, rickshaw pullers. The people’s responses made it to the film’s dialogues. It also blends professional actors with over 350 non-actors on screen and overlays documentary footage with animation and folk art.

It deliberately avoids cliches. “These people are not objects or victims,” says Haksar, 63. “I wanted to celebrate the dignity of labour but also showcase what is happening to the people who work in labour. When you’re lifting up that load for instance, what’s happening to your body physically? What are your dreams? What are your fears? And what are your joys? What comes to you when you’re sleeping because that’s your subconscious mind.”

Like most dreams, theirs are disjointed, interrupted, and emotional. One shows a person walking on a ledge while the other features a giant man the size of the city waving a red flag as a candlelight vigil moves on the ground. In a vendor’s nightmares, he sees his children in his village home, burning.

Several producers turned her down, she says. Many more told her that the script was weird. She still pushed on, raising money by selling her Delhi home to a developer, borrowing from friends and family, and crowdfunding online to complete it.

The film was the only one from India to be included in the Sundance Film Festival’s exclusive New Frontier section in 2019. It has toured the festival circuit since.

At a screening in Brazil in 2019, where the film had Portuguese subtitles, people came up to her and asked, “Are you talking about your country or ours?”. It has provoked discussions about the marginalised. “The feeling, the politics of it is being deeply received,” Haksar says.

Streaming platforms have shied away from the unorthodox story and treatment. But this year, it ran in cinemas in 12 cities and played not just to arthouse cinema aficionados and theatre veterans, but to daily-wage earners, hawkers and other labour classes whose lives form the tapestry of the film.

“We collaborated with NGOs and unions in every city that we released in and we showed it to over 4,000 people,” says Haksar, 63. “It jostled for space between big budget films such as Jurassic World Dominion and Samrat Prithviraj. Prithviraj closed in four days, but Ghode Ko… galloped on.”

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here