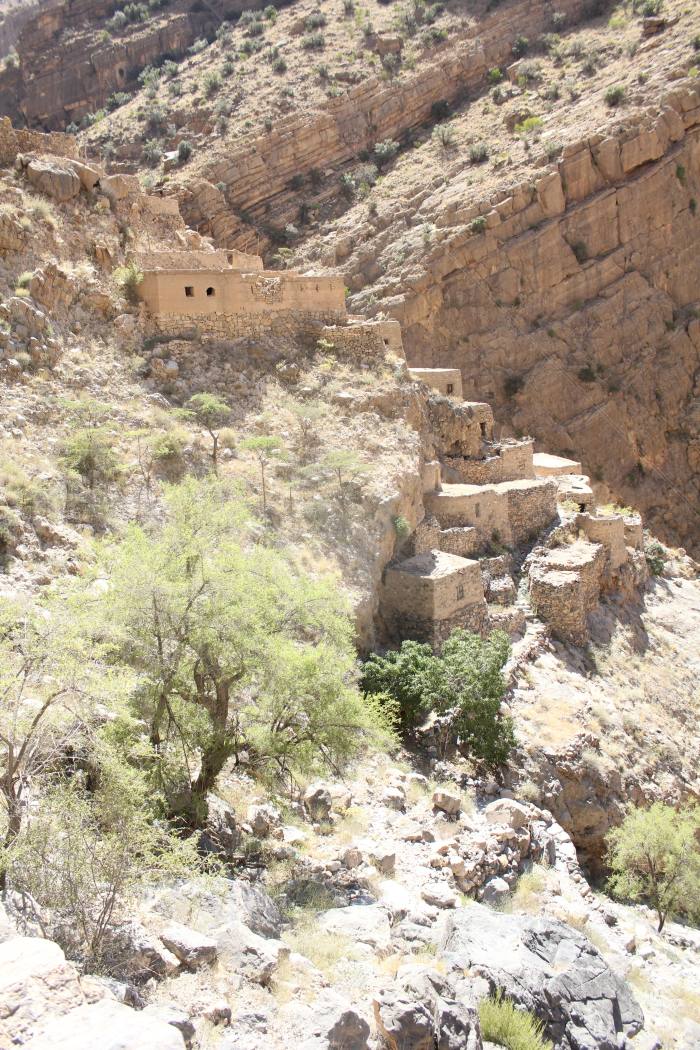

The village had been abandoned for about 20 years. But I found it difficult to imagine anyone had ever lived there at all.

Sab Bani Khamis is set improbably on a narrow ledge of rock in the Hajar Mountains of Oman. Above it, a vertical wall rises to Jebel Shams — “the mountain of the sun” — so-named because its summit is touched by the first and last beams of the day’s sunlight. Below the village looms a roughly 800-metre drop — tumbling sheer into the shadows and silence of an immense canyon. You can look down to see vultures on the wing. You might chew on dates, spit the stones into oblivion — and never hope to see or hear them land.

It had taken an hour and a half for me to walk the donkey track to Sab Bani Khamis. It was also a journey into another age. The houses were small and ancient-looking, with slumped stones and collapsed olive-wood beams. A few pomegranate trees still grew on the old terraces (some of the fruit was rotten). Only the mosque has been well kept, with a pristine copy of the Koran inside. Much of the village is pitched at a 45-degree angle, the gradients seemingly willing you downwards into the abyss. I heard that at one point the young children who lived here had heavy rocks tied to their ankles to ensure they didn’t wander far from their houses.

“The village was a happy place,” remembers Suleiman bin Humaid. “Nobody could ever bother us up there.”

Suleiman is aged about 90. Born in Sab Bani Khamis, he remembers boyhood summers when villagers sang during the fig harvest — and three-day journeys from the mountain to buy flour from the market. For the dozen or so families resident there, Sab Bani Khamis was a sanctuary: the cliffs of Jebel Shams worked as an umbrella against torrential rain, the houses sheltered in the cavity behind sudden waterfalls. Tribal wars never reached these heights.

But there was a different danger. About a century ago, a couple were pulling corn from the lower terrace of the gardens — a shelf of rock cantilevered like a diving board over the void below. One plant was mature and tough. The husband didn’t have the strength to pull it, so his wife showed him how. She lost her balance when it came free. I worked out it would have taken more than 10 seconds for her to fall to the canyon floor, still clutching the crop.

Eventually, the inhabitants of Sab Bani Khamis succumbed to the gravity of modernity. Some 400 years after it was founded, the village was part-abandoned in the 1960s. It was used as an occasional winter home until 2000, when the spring that watered its crops ran dry and the gardens withered. By that point, the Omani government was offering land on the valley floor, and incentives to live closer to amenities and schools. Many former residents now have large air-conditioned houses on the plains. Suleiman, meanwhile, lives in the mountain hamlet of Al Khatim — from here he can still walk the donkey track to his old village among the eyries and the thin air, and visit the pomegranate trees.

“I didn’t want to go and live in the world down below,” says Suleiman. “It is a different life. You can’t let your animals roam. There is not the same freedom down there.”

Sab Bani Khamis is one of many abandoned villages in the Hajar Mountains of Oman. Over a week of walking here, I passed several settlements clinging by their fingertips to the cliffs — places of splintered wood and crumbling clay, hearths blackened by ancient fires. They have a melancholy beauty. But their abandonment also reveals something about Oman, a country that has experienced a transformation as dramatic as any over the past few decades.

I had brought with me Jan Morris’s book Sultan in Oman, the writer’s 1957 account of travelling with Sultan Said bin Taimur on his campaign to assert sovereignty over the Hajar Mountains — then under the control of the rival Imamate of Oman. The Sultan’s forces were backed by the British (who, in turn, were backed by powerful oil interests keen to drill the Omani interior). Morris’s book is open-eyed to this cynical play late in the British imperial chess game. But it is also a lyrical portrait of a place then barely known to the western world — “until now [the Omani interior] had been a populated Atlantis,” she wrote, “an island of hearsay between the desert and the sea . . . less familiar than Greenland or Tibet.”

Morris’s accounts describe communities of cave-dwellers, walled cities whose mighty gates closed with a ceremonial gunshot at dusk, remote regions where tribes prayed towards the sun. The prose feels hard to square with today’s prosperous oil-rich country of multi-lane highways and high-speed internet. But occasionally her descriptions resonate — in mountain villages, on certain lonely shepherds’ trails, in a wadi that my guide suggests we avoid because the djinns (invisible spirits) there get nervous around human beings.

Of particular interest to Morris were the aflaj (singular: falaj) — the man-made water channels that course through the mountains of Oman, trickling into terraced gardens. She observed that to travellers in these parched landscapes, “water had an almost mystical quality, as gold or uranium do to people of other circumstances”.

The falaj in Sab Bani Khamis was dry and broken — only ants streamed along its stones on my visit. But the falaj in the nearby village of Misfat Al Abriyeen is a vigorous, healthy jet, feeding lush plantations of dates and mangoes, winter crops of tomatoes and garlic. Misfat itself is still a village thrumming with life, busy with guesthouses and little museums. After sunburned hours walking through arid mountains, where the only thing flowing is the sweat on your brow, hearing the gurgling of its falaj heralds the entry into a kind of paradise.

“Water is the source of life,” says Yaqoob Al Abri, owner of Misfah Old House B&B. “The mountain is like a giant tank that gives us water even when it has not rained — thanks be to God!”

Aflaj may have been in existence in Oman since the Bronze Age — though their creation is traditionally credited to King Solomon, who on a thirsty journey through Arabia summoned djinns to conjure water from the earth. The falaj at Misfat is a kind that collects water from the innards of the Hajars through a deep, bat-haunted tunnel. Rainwater that might have been percolating through strata of rock for centuries streams into sunlight, then courses through an intricately engineered irrigation system, lapping at junctions dammed with old rags and stones, cascading down a delta of clay and concrete into the gardens. Unlike a river in which tributaries consolidate and gather strength, it is more like a beating heart, pumping life through arteries that divide and subdivide.

As well as irrigating crops, aflaj are used for washing dishes, laundry and human bodies. One evening I wandered upstream along the falaj in Misfat — the mother channel rushing mercury-like under moonlight — to see someone performing ablutions before prayers in the mosque. Silhouetted against the constellations are watchtowers built to guard the channel from saboteurs. Frogs ribbit in the puddles of the overflow.

“When you first see the water rushing down the channel, it is almost as if it is alive,” says Yaqoob. “Every falaj has its own order. It is designed to give everybody a chance.”

Access to aflaj is through a timeshare system — your share of water must be inherited (or purchased from an existing owner; €4,000 will buy you half an hour every eight days for eternity in Misfat). Traditionally, the rotation of the water went in tandem with the turn of the heavens. High on the cliff above the village are eight cairns — when certain stars touched the rocks, dams were opened to switch the flow from one garden to another. Sundials governed the clockwork adjustments of the falaj by day. These days the rotation of aflaj is mostly done by alarm clocks and WhatsApp groups. But spending time in Misfat you grow accustomed to the sweet sound of the water altering course — which sounds like music shifting from one key to another.

Falaj were once a constant from cradle to grave — children learnt to swim in the reservoirs with banana tree trunks as buoyancy aids; the bodies of the recently deceased were cleansed in the cool water. Indeed, the national character has been shaped by the management of aflaj — according to Jeremy Jones and Nicholas Ridout’s A History of Modern Oman “aflaj . . . has given Omani culture a strong material basis for co-operation . . . non-confrontation and consensual decision making”.

But even aflaj are not immune to the creep of modernity. A recent UN report showed that they are now being operated by an ageing demographic. In Misfat, I’m told many young locals aren’t interested in farming any more.

“Once children used to race little boats down the falaj,” says my guide Nawaf Al Wahaibi. “But, of course, now they have video games instead.”

Two years after Jan Morris published Sultan in Oman, British and Sultanate forces laid siege to the last stronghold of the Imamate on Jebel Akhdar (the Green Mountain). This mountain massif truly resembles an immense fortress — its ramparts of rock crenellated with limestone crags, scored with gloomy caves like arrow slits — all of it enclosing a central basin like a castle courtyard. Jebel Akhdar witnessed the final act of a war that helped create today’s Sultanate of Oman — the Special Air Service defeating the Sultan’s enemies, as RAF jets bombed the ancient aflaj.

Today this history is little spoken of — Jebel Akhdar’s lofty heights are now busy with five-star hotels and tourists who come to escape the summer heat of the Gulf. But dotted about the canyons, out of sight of the honeymoon suites and infinity pools, are more phantom villages abandoned in the social upheavals of the 20th century. Here and there are the scars of the war.

My last walk takes me two hours down a steep canyon to reach the village of Masirat Ash Shirayqiyyin — abandoned in the 1990s, when its residents left for new homes beside tarmac roads with mains electricity. Among its huddle of mud-brick houses is the flotsam of past lives: a rusted iron cot, a hurricane lamp, two bottles of Scotch whisky. Tiny windows look over the mountain ridges once patrolled by the SAS, now stomped by goats. I am ready to turn back, when my guide, Said al Riyami, suggests we walk a little further, into the village gardens.

They are, unexpectedly, the most beautiful gardens I visit in Oman — a falaj spilling on to emerald terraces shaded by towering palms, coursing through banana groves where the air quivers with butterflies. We stop and swim in a reservoir of cool mountain water, more perfect than any hotel pool. We steal some of the water to boil cardamom coffee and reflect on the strangeness of this living garden for a dead village — where the ghosts of the recent past feel near at hand.

“I am 40,” says Said. “So I have seen both the old way and the new way of life. The old life was beautiful. But money has changed people.”

These gardens are, we agree, an earthly paradise. Perhaps in our subconscious is an old story about another garden before mortals make the mistake of departing. But in a sense it is a delusion. The flow of Gulf money sustains these remote gardens in the canyon at Masirat Ash Shirayqiyyin. Migrant workers from Bangladesh are paid to do the back-breaking harvesting that locals will not. Helicopters periodically come to drop fertiliser and collect sacks full of dates. Three decades ago, the owners of the gardens chose to live in a place where they can get water with the turn of a stainless-steel tap.

With this thought, I get ready to leave. But before I do, I tear a page out of my reporter’s notebook and make a few right-angled folds. I cast my paper boat out on to the falaj. It catches the water mid-current, and its tiny white sail swoops beneath the palms.

Oliver Smith’s book ‘The Atlas of Abandoned Places’ is out now (Octopus, £20)

Details

Oliver Smith was a guest of Wild Frontiers (wildfrontierstravel.com), which can arrange tailor-made trips throughout Oman, including walks in the Jebel Shams and Jebel Akhdar ranges. Its 17-day “complete Oman” private tour starts at £7,585 per person. For more on the country, see the tourist board website, experienceoman.om

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Travel News Click Here