Through millennia, art has evoked our joy in the touch, taste, smell, as well as sight, of things. The Louvre’s stupendous exhibition Les choses — une histoire de la nature morte (Things — a history of still life) stretches from bread, figs and peaches, enduringly bright and luscious in Roman murals and mosaics, to Felix González-Torres’s memento mori of a slipping pile of Bazooka bubblegum packets, “Untitled (Welcome Back Heroes)”, created during the Gulf war in 1991.

There is hardly an iconic still life in the western canon, it seems, that this mighty museum does not own or cannot borrow (70 museums have contributed): Arcimboldo’s berry-eyed, pear-nosed, mushroom-eared vegetal/human face, “Autumn” (1573); Luis Meléndez’s romantic “Still Life with Watermelons and Apples”, pink flesh bursting out on to a stormy landscape (1771); Giacometti’s dissected head and hand in “Surrealist Table” (1933); pop artist Erró’s Day-Glo satire on supermarket abundance “Foodscape” (1964).

The last significant European still life show was Louvre curator Charles Sterling’s in 1952. This new one is a once-in-a-lifetime sweep: a sensualist’s feast and also, in intellectually playful Parisian tradition, a philosopher’s tale. How we think about things reveals our relationship with the world, our attempts to make sense of it. Still life, the show argues, is not inert “nature morte” (dead nature) but a living form, animated by individual minds and hearts, and by social and scientific forces.

Chardin’s clear-eyed “Dead Hare” and “Rabbit”, with their subtle colour and soft textures, are visual emblems of Enlightenment empiricism. Warhol’s multiple identikit logos in “Coca-Cola” celebrate American democratic consumerism — “no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking”. Recent discovery of the DNA structure inspired Salvador Dalí’s double helix patterns — spiralling balcony railings, twisted silver bowl spinning mid-air — in “Living Still Life” (1956). An 18-metre column hung with assorted packages in African fabrics, Barthélémy Toguo’s “The Pillar of Missing Migrants”, belongs tragically to our own times.

An underlying story is the tremendous victory of secular emancipation, as still life moved from the medieval margins — props of book, candlestick, cushions in Rogier van der Weyden’s “Annunciation” — to slowly occupy centre stage. It was still provocative for Cézanne to astonish Paris with an apple — the fruit on a tilting “Kitchen Table” is the exhibition’s most glorious 19th-century work. But by Braque’s fractured cubist “Bottle, glass and apple” in 1910, still life was fundamental to modernist breakthrough.

Curator Laurence Bertrand Dorléac has a light touch, adventurous spirit and vast erudition. Humour — Meret Oppenheim’s frothing beer mug with furry tail “Squirrel”, Jacques Tati’s discomfiting modernist chair in “Playtime” — leaven her show. Explosive juxtapositions enliven but do not distort a coherent chronological narrative.

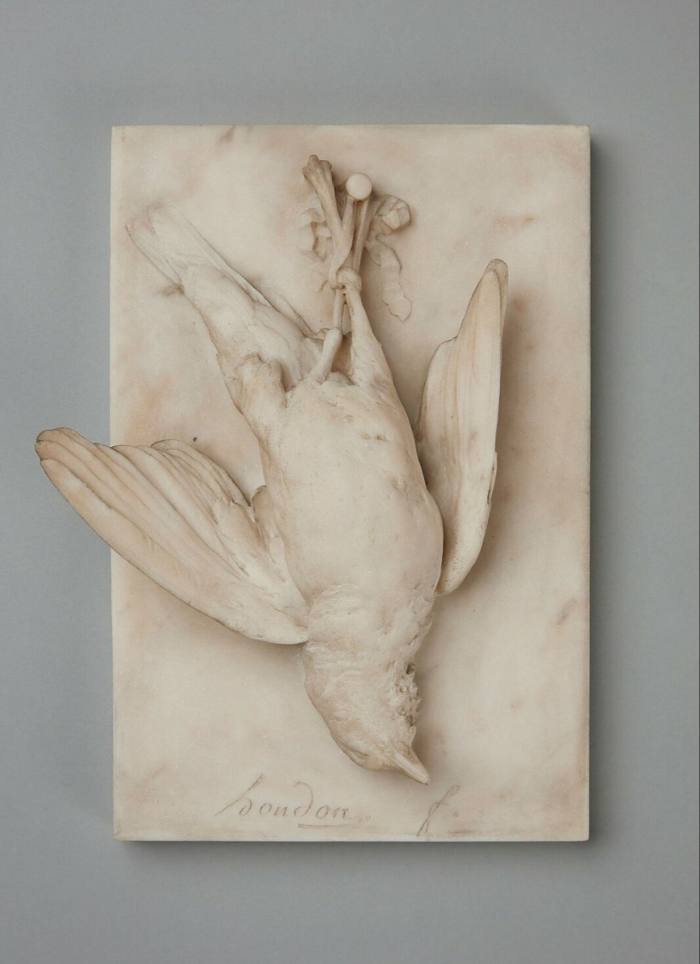

For the section “La Bête Humaine”, positing animal still lifes as stand-ins for human suffering, the Prado has sent Zurbarán’s “Agnus Dei”, a fluffy ram with bound feet, laid out in resigned sacrificial posture, to face Rembrandt’s muscular “Flayed Ox”, the suspended carcass imitating a crucifixion, and Goya’s bloody sheep’s head with doleful expressive eyes in “A Butcher’s Counter”. This sober Old Master room is illuminated by Andres Serrano’s huge glossy photograph, backlit nightclub red, of a decapitated calf casting us a knowing glance from its marble pedestal, “Cadazo de Vaca”. It’s an enthralling confrontation, across centuries and media, between images of matter, mortality, destiny.

Star loans from some 70 museums worldwide allow these rarest of dialogues. From MoMA comes Matisse’s “Still Life after Jan Davidsz de Heem’s ‘La Desserte’” (1915), exceptionally united here with the Louvre’s painting, made in Antwerp in 1640, on which it was based: two majestic depictions of a platter spilling grapes, half-torn brioche, elaborate goblet, embossed chalice, sumptuous tablecloth. De Heem’s equilibrium, mimetic conviction and tactility affirm order and plenty. Matisse in wartime dissects the illusion, jumbles planes, shatters space, destroys perspective, emphasises jagged edges, unstable arrangements. Yet brilliant spring colours, radiant light greens and turquoises, sound notes of hope.

Matisse is the marvellous interloper in a key section exploring how still life took off as an independent genre in the 16th-17th century Netherlands. Frans Snyders made cabbages and cauliflowers, their leaves unfurling like dashing coiffures, the chief characters in a densely worked monumental “Still Life with Vegetables”, while relegating the farmers harvesting them, tiny and faint, to a corner: a new reign of things. Joachim Beuckelaer’s immersive panoramas “Fish Market” and “Butcher’s Shop” pull us into the milieu of trade; their detailed bounties — glistening salmon, sausages dangling over pigs’ trotters — surge towards us, triumphant products of an affluent society and dawning materialist worldview.

Artists both depicted and joined a mercantile culture of exchange, accumulation, display, and among those seizing the fresh opportunities were women, historically excluded from studying the human figure. In Louise Moillon’s “Bowl of Cherries, Plums and Melon”, each element conveys its own strength and particularity within a supreme harmony. Clara Peeters, in her distinctive, witty “Still Life with a Sparrow Hawk, Fowl, Porcelain and Shells”, perches the predator, alert and vivid, on the slaughtered fowl.

Manet called still life “the touchstone of the painter” — a genre allowing intensely personal modes of representation. Courbet’s “Trout”, open-mouthed, out of the water, once vigorous, now trapped, is a self-portrait of the artist imprisoned after the Commune. Joan Miró’s psychedelic “Still Life with Old Shoe” is a traumatised reaction to the Spanish civil war: its opaque/translucent peaks and hollows read like a melting landscape.

Manet’s own fluid late still lifes are a dying man’s musing on the quotidian — exquisite, lucid, things pared to their essence. “The Lemon” sparkles against a varnished black dish. “Bunch of Asparagus”, each stalk a nuanced streak of cream, yellow, purple, on a bed of dark leaves, was bought by collector Charles Ephrussi, who overpaid. In response, Manet painted him a single stem, “Asparagus” — “there was one missing from your bunch”: a yet richer blend of lushness and minimalist rendering.

Still life has special affinities with minimalism. Throughout the show are paintings — Adriaen Coorte’s “Six Shells on a Stone Table”, each encrusted form luminous against a dark ground; Giorgio Morandi’s pale jars and cake moulds “Still Life”; Miquel Barceló’s shadowy “Grisaille with Swordfish” — whose simplicity yet authority stops you in your tracks, stirring a sense of mystery, the enigma of the visible.

“In our twittering world, artists invite us to pay attention to everything that is silent and minuscule,” Dorléac writes. “In giving form to the things of life, the things of death, they talk of us, of our history . . . our attachments, fears, hopes, caprices, follies.” She begins her catalogue paying homage to Sterling’s exhibition; hers will surely be remembered for as long.

To January 23, louvre.fr

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here