South Korea is no longer the country most riveted by K-pop, at least not on Twitter. According to a 2021 Twitter report, for the second year in a row, Indonesia topped the list of countries with the most #KPop tweets. The Philippines, South Korea, Thailand, the US, Mexico, Malaysia, Brazil, India and Japan, in that order, made up the rest of the top ten.

This is a big win for the tiny nation. Once known mainly for making computer chips and cars (South Korean giants include Samsung, LG, Hyundai), the country first began exporting its squeaky-clean pop-culture brands in the early 2000s, with the first wave of K-serials washing over Japan. Many of these shows — tales of love, heartbreak, betrayal — had original soundtracks made up largely of soft, heartfelt ballads. In 2003, K-pop made its first major inroads into Japan, as Korean singer BoA climbed the charts. Bands such as TVXQ and BigBang followed; then came early sensations such as Super Junior, Girl’s Generation and Kara.

Facebook, Twitter and YouTube helped expand the overseas market. Then, in 2012, rapper Psy released Gangnam Style, the first music video ever to hit 1 billion views on YouTube.

As he performed his trademark horse-riding step with pop icon Madonna and US President Barack Obama, the growing number of entertainment companies operating in South Korea sat up. They’d been focusing on South Asia; clearly, it was time to look beyond.

Over the intervening decade, K-dramas have swept up global audiences. Korean films have won awards and shattered the language barrier. K-pop has become an indisputable global phenomenon. In fact, the year after Gangnam Style, BTS was born, with its carefully crafted image of gentle boys looking to spread kindness, self-belief and other good values around the world.

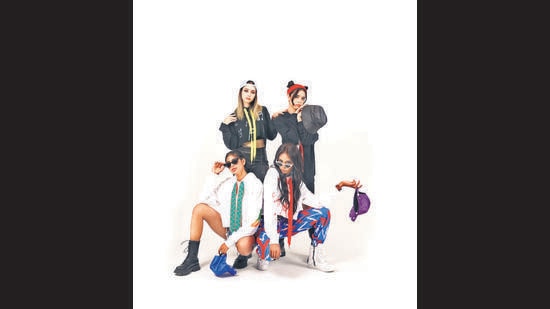

Now, K-pop is embracing a new change, recruiting members for major bands from across races and cultures. The latest Indian to join a K-pop band, Sriya Lenka, 19, was inducted into Blackswan this May. She’s part of a shift that’s been increasingly visible over the past two years.

Blackswan, for instance, was founded in 2020 with three Koreans, one Brazilian and one Belgian. The band now has four members, from Senegal, Germany, Brazil, and India, and no South Koreans. Meanwhile, the entertainment companies behind K-pop bands are setting up franchises in other countries with, for instance, all-Japanese or all-Chinese members.

“K-pop is no longer just a Korean music genre,” says Philip YJ Yoon, managing director with DR Music Entertainment, which manages Blackswan. “K-pop already has a massive global audience, and I believe it is natural for the members of K-pop idols to be globalised as well.”

Blackswan was conceived as a global band, YJ Yoon adds. The idea was that “it would be nice to impress people around the world who thought they could never be in the K-pop industry due to their race, colour etc. They can now dream of becoming K-pop idols as long as they have a determined goal and a personality that suits.”

It helps that the bands have a rapid turnover, when it comes to members. The average term is seven years. After their contracts expire, most K-pop stars go on to pursue careers as solo artists, models, actors or social media influencers.

The cyclical change keeps the bands from becoming too strongly identified with individual members. And it keeps the individual members in check, which is vital, because K-pop stars aren’t just “cute”; they’re meant to be healthy, wholesome, respectful of cultures (their own and others’), expected to set a good example through their lyrics and their lives. They can’t be seen smoking, brawling, inebriated, unkempt or even heartbroken.

In the works

So what is it like inside this massive, well-oiled machine? Discipline is sacred. For eight months, Lenka has been living in Seoul, training for her debut. She spends 10 to 12 hours a day, six to seven days a week, studying Korean, working out, taking choreography and singing classes and attending live practice sessions.

Originally from Odisha, Lenka is trained in Odissi and hip-hop and believes it was her dance skills that stood out among the thousands of audition tapes from India. “There were a lot of applicants from India, and Sriya’s skills and attitude were the best among them,” says YJ Yoon.

There was a six-month probation period as training tested her skills and discipline.

“Those six months made me more disciplined and made me believe in myself,” Lenka says. “My dancing and singing skills have improved drastically. We sing while running to stabilise our voices and there’s been a lot of focus on working out.”

Not everyone is as sanguine about the process. Priyanka Mazumdar, a 25-year-old from Assam who joined the multi-national South Korea-based band Z-Girls in 2019, calls her race to the debut survivalist.

“It is not necessarily beautiful but rather harsh and sometimes unhealthy. If you can find the balance, it is worth it. It has made me more confident, always challenging me to be a better version of myself,” she says. “The K-Pop training may negatively affect both physical and mental health given the diets, continuous training, schedules and constant pressure. But in the K-pop lifestyle, you get to unlock your potential and improve in every aspect.”

Z-Girls is a good example of the global juggernaut that K-pop has become. Z-Girls and Z-Boys make up the coalition Z-Stars, managed by Divtone Entertainment. The band has members from Japan, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam, but, by design, none from South Korea. There are plans to add members from other countries.

It began as a way to celebrate Generation Z, with each member representing a different country, Mazumdar says. “Z-Pop aims to bring the world closer together through music. The motto is ‘Beyond borders: one culture, one consciousness’.”

What’s next? Solo “Korean” stars from other countries, as South Korea invites the world onto more of its screens. Actor Anushka Sen, 19, for instance, has been signed by Asia Lab, a South Korean entertainment company. Her first show, God of Travel, a travel show focused on South Korea, was released on YouTube in June.

“Typically, collaboration with global stars or markets was focused on marketing Korean content to wider audiences with an eye on revenue,” says Lee Jung-Sub, founder and CEO of Asia Lab. “The new Korean wave will emphasise understanding of other countries as well, and reflecting other countries in local content. I believe that understanding one another and being together is the key to being truly ‘global’.”

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here