Deborah Roberts seemed to explode on to the art scene only recently with her poignant collages of black life, but the 60-year-old African American has been working assiduously as an artist for three decades. Until a few years ago, she supplemented her income working in a shoe-shop. “I can show you six ways to tie your laces,” she says. Now her work commands tens of thousands of dollars and she counts museums, galleries and art buyers such as Beyoncé among her collectors.

As in previous exhibitions, I Have Something to Tell You, her latest show at the Stephen Friedman Gallery in London, focuses on black children, their early sexualisation and criminalisation. Given the seriousness of her art, it’s surprising to meet a smiling (behind her Covid mask) Roberts as her 12 new works are installed. Despite the decades-long wait for financial reward, the graceful artist gives the impression of being built for success.

Many of the large canvases are mixed-media portraits of black bodies, boys and girls. The centrepiece, The Body Remembers, is a searing response to the strip-search by the Metropolitan police of Child Q, the 15-year-old girl at an east London school who was falsely accused of possessing marijuana.

I ask Roberts about her journey from full-time painter to revered collagist. Norman Rockwell’s tender portraits of everyday life in the US were an early inspiration, she says. “I knew he was painting about experiences I was having as a child, but I didn’t see people of colour in them.” Apart from the famous civil rights painting, The Problem We All Live With, she says, “there were only one or two with African American children”. She decided to paint her own versions of everyday life: “I wanted everyone to have the kind of childhood that Norman Rockwell pictured.”

As a painter, she had a steady number of commercial clients but, by the early 2000s, a change came over her work. A journal commissioned a jazz piece, she says, “but when I began painting, the body fractured, the imagery, the lights, everything. The end result wasn’t this sultry singer on stage – the body no longer looked human.”

From then on, Roberts began experimenting, layering her canvases with paint and collage. “My first collage was an accident. I was cutting up faces to lay them out and they landed on each other and I thought: ‘Oh my God, that’s it!’ It allowed me to talk about blackness in a way that wasn’t talked about before.”

Her mission to humanise black girls in art peaked when she heard about Child Q. “That story enraged me,” says Roberts. “That experience will change her life. We try so hard to fight for our beauty.” She shakes her head. “To take a child and to strip her of dignity and humanity. It touched me because generational trauma is passed on in black people. That trauma is in her now. That’s why the piece is called The Body Remembers.”

The work, inspired by the Child Q case, shows an unidentifiable young girl, with a collage of anonymous faces, who is not yet stripped of her clothing, but bending over as if she’s about to be internally examined. “It’s the worse thing that could possibly happen to you besides rape,” she says. “To me, based on our history of enslavement, it was a way to break her, the way enslaved people were broken by overseers. That’s why I put multiple anonymous faces on the work, because the trauma she experienced is not new.”

Roberts sees the work as a tool towards enlightenment: “The girl’s wearing red leggings because she was on her period. I put the cherries on her blouse to reflect lost innocence. The stripes on her sleeves suggest a prison uniform, because black people carry that false notion of criminality wherever we go.” Roberts reflects on the collage of faces: “There’s the profile looking down from humiliation and shame. There’s another face where she looks directlyat you, like – how can you be doing this to me? The police treated Child Q as if she was subhuman. They didn’t see themselves or their daughters in her.”

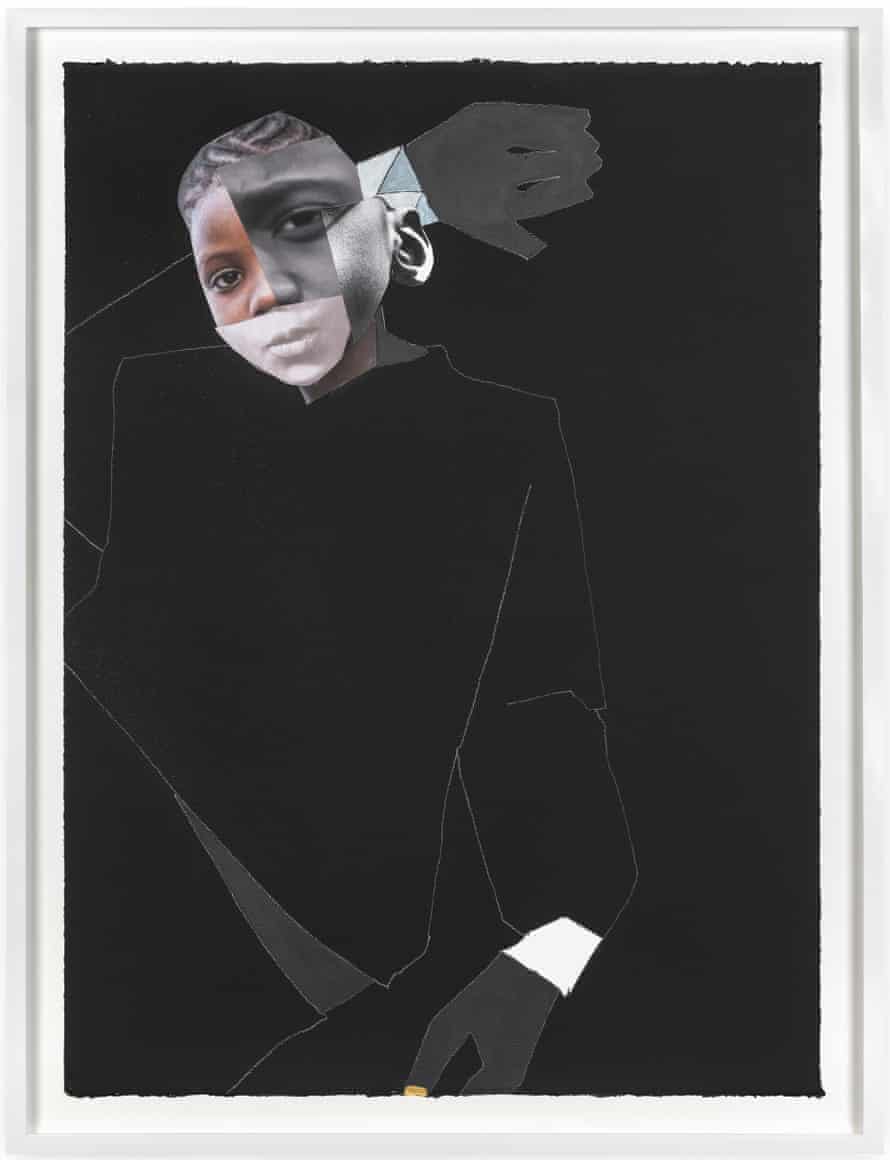

This notion of black invisibility runs throughout the exhibition, depicting black children with contorted bodies almost as phantoms on black canvases. “It’s the idea of being absent and present simultaneously,” says Roberts. “I put chalk around the bodies, like when someone’s murdered. I make the face really clear but fade the rest of the body, as if they’re disappearing right before our eyes and no one cares.”

Black absence is also an element of the history of western art, says Roberts. Her witty work Yo Picasso speaks to her engagement with Picasso’s African period and the art she thinks he “arrogantly appropriated”. Roberts says: “In Yo Picasso, this black kid is lying down with hands cuffed behind his back saying, ‘Yo Picasso, you have rendered me meaningless, purposefully.’ The fractured face of my portrait is in dialogue with Picasso’s fractured cubist faces. That’s the way white people see us – as fractured. They don’t see the whole person.”

When my eyes meet those of the humiliated but defiant proxy for Child Q, I confess to Roberts that it leaves me feeling like a voyeur or complicit – it’s ambivalent. Roberts nods and sighs: “I guess that ambivalence goes back to my childhood, to the withering gaze of a teacher who habitually grabbed my face. Still today, I don’t look people directly in the face. When you lower your eyes, it tends to give them more power over you.”

As the father of black children, I say, it resonates with me. “Right, we have a shared history. As James Baldwin once said, ‘If they take you in the morning, they will be coming for us that night.’ The world tells you that you are ugly. It makes you despise yourself. I’m trying to show the beauty and the glow that exists in black children, to lift the veil on their lives.”

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Education News Click Here