Before De La Soul, says Hank Shocklee, “‘beautiful’ and ‘rap’ weren’t two words that went together.”

Shocklee would know: As a founding member of Public Enemy’s production team, the Bomb Squad, he’s as responsible as anyone for shaping the blaring, dissonant, pugnacious sound of hip-hop in the mid- to late-1980s, when the music “was almost like a football game — just smacking you upside the head,” as the producer puts it.

Yet less than a year after Public Enemy released the pummeling “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” — and N.W.A the furious “Straight Outta Compton” — the three middle-class misfits of Long Island’s De La Soul dropped 1989’s “3 Feet High and Rising,” a lush and whimsical debut that “wasn’t abrasive or agitated or in your face,” Shocklee says. Intricately assembled by De La Soul and their producer, Prince Paul, from dozens of samples of far-flung tracks by the likes of Steely Dan, Liberace and Hall & Oates, the LP showcased a more playful and melodic idea of hip-hop, with the rappers musing on identity and friendship and lust in a coded language over welcoming, lightly psychedelic grooves riddled with hooks.

“It gave rap a different sonic texture — a mushrooms-and-daisies kind of vibration,” Shocklee says of “3 Feet High and Rising.” “Rap at that time was all about confrontation, and it was pretty much all yelling. You wanted your voice to be heard, so you were shouting it out. But these guys had a different take. It was very, very laid-back. And, man, it was just beautiful.”

The album was an instant success with listeners and tastemakers, topping the Village Voice’s annual Pazz & Jop critics poll and spawning a No. 1 hit on Billboard’s R&B chart with the ebullient “Me Myself and I,” which went on to earn a Grammy nomination for rap performance. (Young MC’s “Bust a Move” ended up winning over both “Me Myself and I” and Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power.”) Longer-term, the innovations of De La Soul — Kelvin “Posdnuos” Mercer, David “Trugoy the Dove” Jolicoeur and Vincent “Maseo” Mason — “enlarged the cultural tent of what hip-hop could be and who saw themselves in it,” says author and professor Dan Charnas, making room for future risk-takers like Outkast, Kanye West, Lil Yachty and Tyler, the Creator.

“If you wanna talk about hip-hop and its 50th anniversary” — as many are this year, half a century after DJ Kool Herc rocked a back-to-school party in the Bronx in 1973 — “one of the reasons that hip-hop could grow and mature as much as it did,” Charnas adds, “is De La’s aesthetic and musical expansionism.”

For all its influence, the group’s music has been frustratingly hard to hear in recent years, the unhappy result of a series of record-industry disputes that kept much of its catalog off streaming platforms including Spotify and Apple Music. But that’s finally set to change on Friday with the overdue digital arrival of De La Soul’s first six LPs, which in a tragic twist comes just weeks after Jolicoeur’s death last month at age 54.

In an Instagram tribute to his late bandmate, who spoke about his struggles with congestive heart failure, Maseo wrote, “On one end I’m happy you no longer have to suffer the pain of your condition but on the other hand I’m extremely upset at the fact that you’re not here to celebrate and enjoy what we worked and fought so hard to achieve.”

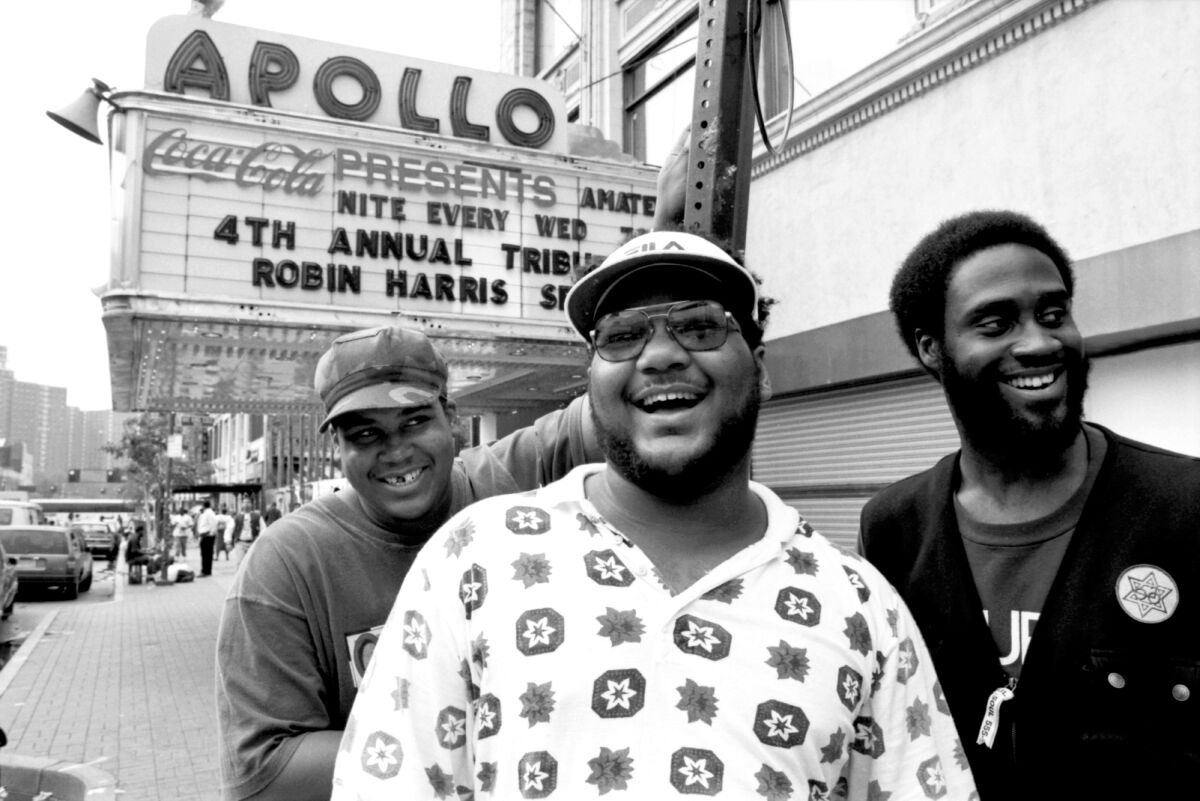

De La Soul outside Harlem, New York’s Apollo Theater in 1993.

(David Corio / Getty Images)

Why precisely De La Soul’s classic albums took so long to make it to streaming — in addition to “3 Feet High and Rising,” Friday’s release will include 1991’s “De La Soul Is Dead” and 1993’s “Buhloone Mindstate,” among other titles — is a complicated story involving sample-clearance issues and disagreements over money between the trio and its longtime label, Tommy Boy Records. The sale in 2021 of Tommy Boy to the music company Reservoir Media for a reported $100 million is apparently what unstuck the deal, according to Dante Ross, who signed De La Soul and worked as the group’s first A&R rep before going on to shepherd the careers of Brand Nubian, MF Doom, Busta Rhymes and others. (He’s the Dante affectionately ribbed as “a scrub” in a song from “3 Feet High and Rising.”)

“But it had always seemed inevitable that it would happen one day because of public demand,” Ross says.

To dive back into De La Soul’s early music today, when the phrase “information overload” gets you about halfway to the experience of scrolling through TikTok, is to marvel at the prescience of the madcap sonic approach — the anything-goes flattening of old hierarchies of taste — at play in a song like “The Magic Number,” which mashes together bits of Syl Johnson’s “Different Strokes,” Led Zeppelin’s “The Crunge” (via a mid-’80s Double Dee & Steinski track) and the soundtrack from the kiddie-TV special “Multiplication Rock.”

“In rap, you always knew where you were gonna get your samples from, and at that time it was funky, hard-driving R&B,” Shocklee says. “Then there were areas you didn’t really go into — more folky things, for instance. But [Prince] Paul used Johnny Cash and he used the Turtles. He sampled things that weren’t our first impulse when we were going to look for a sample.” (In 1991, the Turtles sued De La Soul for more than $1 million for using a snippet of the ’60s band’s “You Showed Me” on “3 Feet High and Rising.”)

Shocklee says the freewheeling sound of De La Soul’s debut inspired him to think more broadly for Public Enemy’s 1990 LP, “Fear of a Black Planet.” “I was looking for different textures, different emotional sides of the tapestry, whether it be some of the Beatles stuff we used or things I’d consider to be a bit more esoteric,” he says. “It was like, OK, now we have the liberty to move in another direction because these guys came out with a whole different frequency.”

Says Ross: “Suddenly people who made beats realized they could sample a Carole King record.”

The exec, who attributes De La Soul’s omnivorous taste in part to the members’ growing up listening to New York’s Top 40 WABC radio station, points out that Posdnuos, Trugoy and Maseo “were more involved in their production than a lot of people knew. They had records and they knew how to use equipment. Paul sorted things out; he cleaned things up. But I was there when Pos made ‘Eye Know,’” he says of the tender and funky “3 Feet” single. “He borrowed my Lee Dorsey record and made that s— himself.” (Prince Paul is still active and worked recently with Damon Albarn‘s Gorillaz, who featured De La Soul on the Grammy-winning “Feel Good Inc.” in 2005.)

Asked to compare “3 Feet High and Rising” to 1989’s other landmark work of sampling — “Paul’s Boutique” by his pals the Beastie Boys — Ross says, “Well, for starters, De La Soul are just rapping better than the Beastie Boys. It’s more poetic, more original. The Beasties were working off a paradigm that was written by Run-D.M.C., and De La Soul was working off a paradigm written by De La Soul.”

But he also identifies a distinct attitude in the sampling. The Beastie Boys, who made “Paul’s Boutique” with the Dust Brothers, “were really trying to show you everything they could do: ‘Look at me! Look at what I got!’” Ross says. “Whereas De La Soul was much more natural and organic. It didn’t have that show-off feel to it.”

Indeed, the trio’s relative gentleness on “3 Feet High and Rising” led some to “view them as soft,” says Charnas. “Not the people really in hip-hop — everybody in hip-hop loved De La Soul — but idiots in the hinterland into toxic masculinity.” The group’s tie-dyed fashion sense and use of flowers and peace signs established an idea of De La Soul as “the hippies of hip-hop,” as Arsenio Hall famously introduced them on his TV show; an advertising campaign explicitly targeted white record-store shoppers with the slogan “I came in for U2 — I came out with De La Soul.”

The members quickly tired of the image. “People questioned their Blackness, which they didn’t appreciate,” Ross says, adding that “they were known to hand out a couple of knuckle sandwiches along the way.” De La Soul’s “3 Feet” follow-up made the group’s feelings clear: Darker and more biting than their debut (even as it kept up the dense patchwork of samples), “De La Soul Is Dead” pondered drug abuse and the obligations of fame amid a running meta-narrative about whether or not the band had fallen off; as with “3 Feet’s” anticipation of late-stage social media, “De La Soul Is Dead” feels now like it was setting the table for the brooding self-awareness of a project like Donald Glover’s “Atlanta.”

Ross, who by the time of the album’s release had moved from Tommy Boy to a gig at Elektra Records, heard “De La Soul Is Dead” as a “middle finger to the label” for perhaps leaning too heavily into the hippie angle. “I envisioned Tom Silverman squirming when he heard the title, which is always a fun thing to do,” he says of the Tommy Boy founder, with whom De La Soul has fought over contract matters.

De La Soul performing in 2017.

(Jack Plunkett / Invision / AP)

To Charnas’ ears, “De La Soul Is Dead” reflects the group’s exhaustion from “pushing against the status quo of hip-hop, which was very taxing to them.” At the point of its release, he adds, “the culture is already moving in a different direction. Cypress Hill is introducing this weed-induced somnambulance, and Dr. Dre is about to create the G-funk thing.”

In a way, though, being backed into a corner turned out to be a boon of sorts for De La Soul, which Ross places in a lineage of “great Black outsiders from Sun Ra to Rammellzee to Parliament-Funkadelic to Pharoah Sanders.” Rather than calling it quits after “De La Soul Is Dead,” the group continued to explore with the jazzy “Buhloone Mindstate” and the mournful yet hard-hitting “Stakes Is High.” In an art form only now entering middle age itself, De La Soul stuck together to become a model of endurance, which, for Shocklee, “is what puts them in my hall of fame,” he says.

“That’s why the passing of Dave blew my mind, because it happened right as this group that was the pinnacle of everything a group should be — right when they were about to have yet another rebirth.”

Will the music’s availability on streaming, which it’s celebrating with a tribute to Jolicoeur on Thursday night at New York’s Webster Hall, foster a connection with a new generation of fans? The group’s most recent album, 2016’s “And the Anonymous Nobody…,” made a minimal impact (though the trio remained a reliable live draw through last year). And nobody in hip-hop right now really sounds like De La Soul, which of course is a sign of the genre’s health — of its persistent dedication to the kind of change De La Soul embodied from the beginning.

Yet the group’s legacy can be felt, even if indirectly, in rap’s increasing emphasis on melody and in its ever-widening emotional bandwidth; more important, the trio’s classic material can still stop you in your tracks, as when “The Magic Number” cropped up in 2021’s blockbuster “Spider-Man: No Way Home.”

“It remains to be seen whether the music will translate to the youth,” Ross says. “But anyone who makes smart, cerebral music within the idiom of hip-hop — whether or not they know it — they owe something to De La Soul. I don’t think that’ll ever change.”

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Music News Click Here