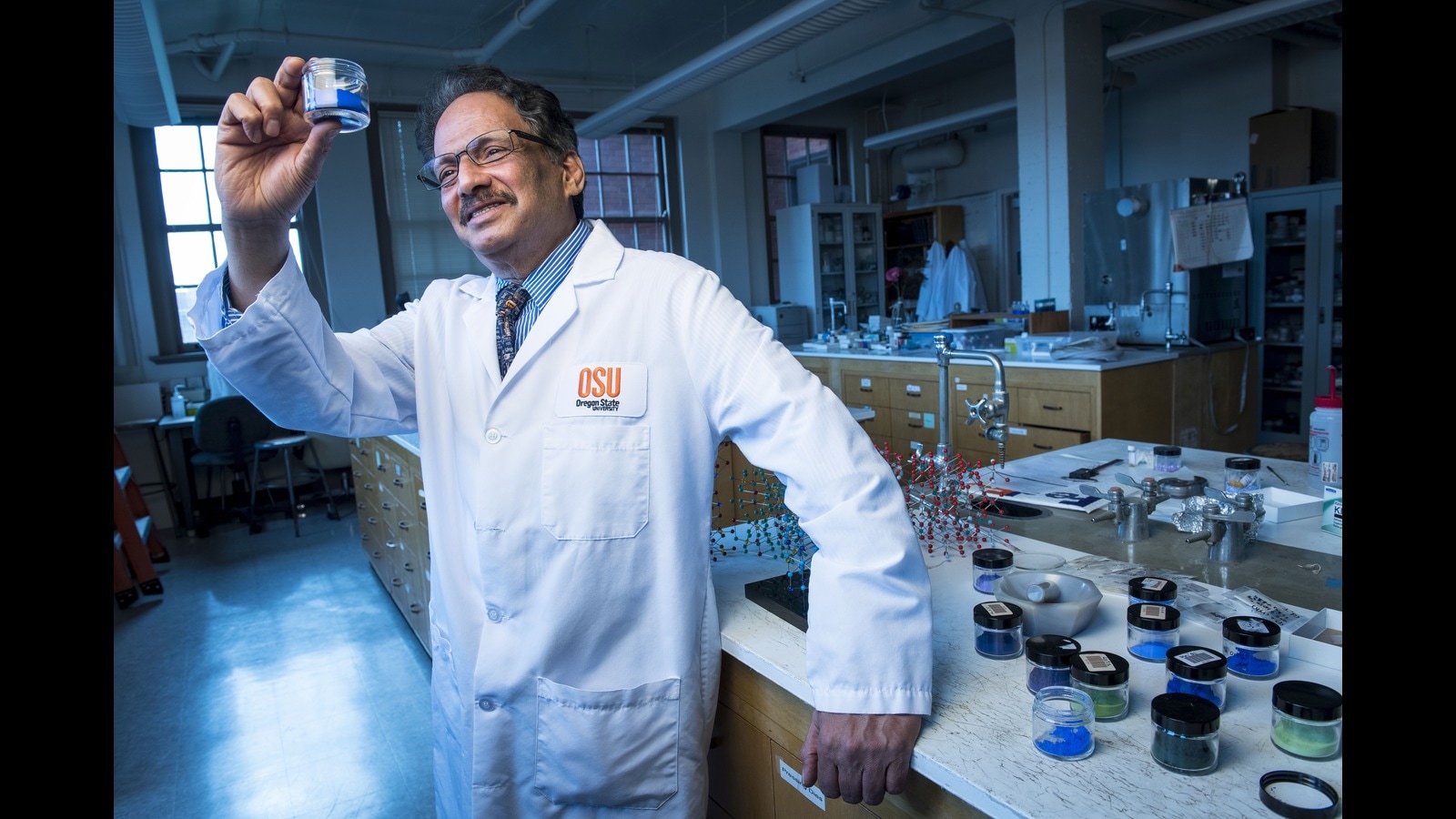

On a day he will never forget, Mas Subramanian headed to his lab at Oregon State University in the US. At the time, 2009, the world hadn’t seen a new blue pigment in at least 200 years. The Madras-born professor and chemist wasn’t expecting to either.

He liked chemistry. He thought of it as “playing with the periodic table of elements”.

His team was using a National Science Foundation grant to research materials that could store data better. They’d been heating the chemicals yttrium, indium and manganese oxides at 1,260 degrees Celsius in the lab’s furnace for 12 hours. “I was expecting it to turn black or grey,” recalls Subramanian, now 67.

But when a research student drew the sample out, Subramanian’s jaw dropped. The incinerated chemicals had turned instead into a clean, vivid blue. “That blue was dazzling. I don’t know what four-letter words I must have used that day. I was awestruck,” he says.

Subramanian was better-placed than most chemists to recognise, right away, that this was no ordinary blue. He’d worked for years with the chemicals multinational DuPont and handled a range of unusual materials. He has seen innovations in yellow and green. Blue, he knew, was among the hardest colours to create artificially — it occurs so rarely in nature.

He didn’t sleep that night, he says. The next day, like any man of science, he set out to replicate his experiment to see if it would yield the same result. It did. He had created the first synthetic blue since a cobalt was developed in France in 1807.

“There was no mention of pigments in our proposal for the grant,” he says. This was an entirely separate triumph.

Subramanian named the pigment YInMn Blue after its parent chemicals, and set about acquiring a patent. Further experiences revealed that the pigment, which absorbs red and green wavelengths while reflecting blue ones had other useful properties. Unlike cobalt, which is toxic if consumed, YInMn Blue was safe. It didn’t fade or release byproducts. And it was the first blue that reflected infra-red radiation, meaning a car or home painted in it would absorb less heat on a sunny day. “It’s not just a pretty face,” Subramanian says.

Every year since, his work has attracted more attention. The Subramanian team received a patent for the blue in 2012. The US approved it for industrial use in 2017, and for commercial use last year. This year, a limited-edition batch of YInMn Blue acrylic paint went on sale. At $179.40 (nearly ₹13,500) for a 36gm tube, it’s more than most artists’ materials cost. And yet, they sold out.

Meanwhile, the professor has a new project. He’s won a new grant from the National Science Foundation — this time to create a range of synthetic colours based on the YInMn principles. “These are pigments for climate change, stable paints that can help offset the heat-island effect in cities. Who thought that pigments could be used for this? It’s opened up a whole field of study,” Subramanian says.

The team has had success with purples and greens. But creating a bright, inorganic, non-toxic, durable red has been a challenge. They’ve managed a deep orange so far, and Subramanian seems sure he’ll coax a red from the furnace eventually.

Colourmaking has changed the chemistry of his mind too. “It’s opened me up to culture and history,” he says. “At museums, I’m looking at Medieval and Renaissance works — Vermeer, Monet — and I’m wondering why they used the blues they did.” His wife Rajeevi Subramanian, an IIT-Madras alumna, a chemist and an artist, uses the pigment when she paints.

Earlier this year, a first-grader sent him a handwritten note expressing delighted interest in his work. “It made me happy beyond imagination,” he says. “It’s not easy to understand most things scientists do. But this? Every generation is interested in it. Growing up, I wanted to be an actor. It seems fame found me anyway. And this is enough discovery for a lifetime.”

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here