I arrived in Washington DC in heat that made the air barely breathable and the outdoors scarcely habitable. Fortunately, there was the National Gallery of Art, where I spent the daylight hours hiking from show to climate-controlled show. Rarely has art seemed so necessary to survival.

That flight to the great indoors is a move the photographer Robert Adams would scorn. American Silence (to October 2) spans the six decades when he took his camera out under the country’s vast skies and invariably found that, here below, people ruin everything. Most of his landscapes deliver a sermon, always the same one: we have taken an Edenic planet and paved it over, ploughed it under, cut it down and corrupted it with ugliness, waste and poison. The pictures may be silent but that doesn’t save them from stridency. Adams once considered going into the Christian ministry; instead, the camera became his pulpit.

In a few fierce photographs, though, silence stalks the sublime. He chased revelation in the dark empty streets of Colorado in the 1970s and found it in a white clapboard house floodlit by a streetlamp. Shadows of leaves from a nearby tree dance across its facade like night spirits, while a window opens on to ordinary lives. Houseplants bedeck the sill, tchotchkes line up along a shelf and the shadow of a figure hovers at the heart of it all. The dwelling is a shining totem of humanity surrounded by impenetrable darkness. Adams’ picture captures the spirit of nocturnal rambles, a sense of stumbling on some perfect alchemy of loneliness and peace, voyeurism and empathy.

These night-time shots are anomalously romantic. When Adams moved to Denver as a teenager in 1952, he fell in love with the prairie encircling the city, and for a time he specialised in flat expanses with sensationally expressive skies. The built environment intrudes only lightly in these scenes, often as plain white structures endowed with human dignity. In one image, a billowing plain is cut off by a wooden structure that edges into the frame, its stiff armature an answer to the flatness of earth and the immensity of sky.

But Adams was already disillusioned by Denver’s ruthless suburbanisation. Tract homes overtook the land like carbuncles, sprawl spoiled virgin fields, smog smudged clear vistas. In increasingly dyspeptic pictures, he documents refuse on the grassy verge of the interstate or next to a fast-food parking lot. He builds his case against humanity in cold, disgusted — if sporadically beautiful — photos.

The farther he wandered, the more he saw the same depredations. He reserved a special revulsion for the debased Garden of California and the clear-cutting of old growth forests in Oregon, where he moved in 1997. A denuded Oregon hillside fills an entire frame, flaunting its despoliation. Adams withholds any consolation, even a strip of unchanging sky. He aspired to document without comment, free of emotional overlay, but he couldn’t help himself. Rage crept in.

At the other end of the museum, we move back indoors, where the domestic interiors of late 19th-century London come as a relief from Adams’ existential gloom. A small suite of galleries embraces The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler (to October 10), a little gem of a show that delves into the fruitful relationship between artist and muse. Whistler focused the world’s attention on his dandyish persona (“Wait till you see me in an amazing hat!” he wrote. “I am going to seem something quite new in London!!!”), feisty egotism and waggish provocations.

But this show shifts the limelight away from him and on to the mysterious and ultimately elusive model who for 20 years was also his lover and business partner and mother to the child he fathered with another woman. Whistler trusted Jo Hiffernan completely, making her the sole heir of his estate. (She never got to benefit from that provision, though, since she died before he did.)

Born in 1839 to poor Irish parents who transplanted the family to London, she met Whistler at 21. Uneducated but keen, unrefined but charming and, of course, beautiful, she immediately entranced him. “She has the most beautiful hair that you have ever seen! A red not golden but copper — as Venetian as a dream!” he wrote to a friend. She starred in his etchings, paintings, drawings, inciting a torrent of creativity.

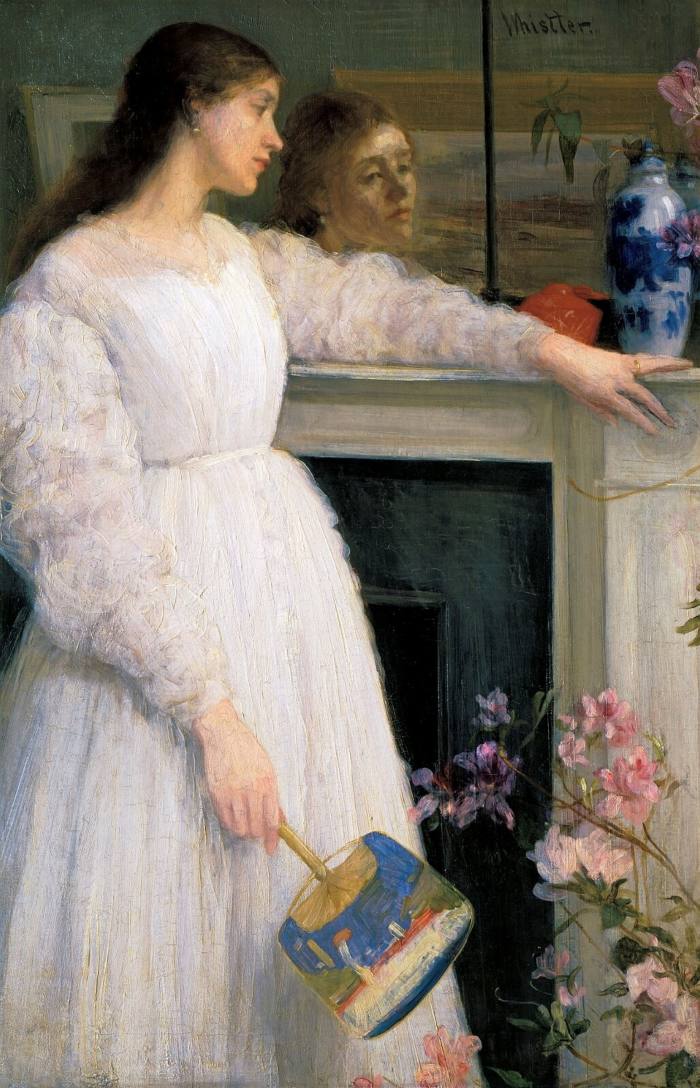

Yet this ubiquitous presence also disappeared, looking so different in each picture that she might have been a dozen different women. “Symphony in White, No 1: the White Girl” is the most familiar and deceptively intimate. A pale-skinned Hiffernan in a tufted lace dress stands before a snowy background, gazing at something we cannot see. The title stresses Whistler’s pugnacious contention that art is a purely formal enterprise, unconfounded with “emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism”. Hiffernan, despite the idiosyncrasies of her wide blue eyes, slightly overlarge mouth and cascading coiffure, remains a cipher.

“The White Girl” reappears in two other quasi-monochrome “Symphonies”. In “No 2”, she poses next to a mirror, wearing a different expression from her reflection’s. The unmediated side we see looks aloof, almost vacant, while the one in the mirror betrays a deep melancholy.

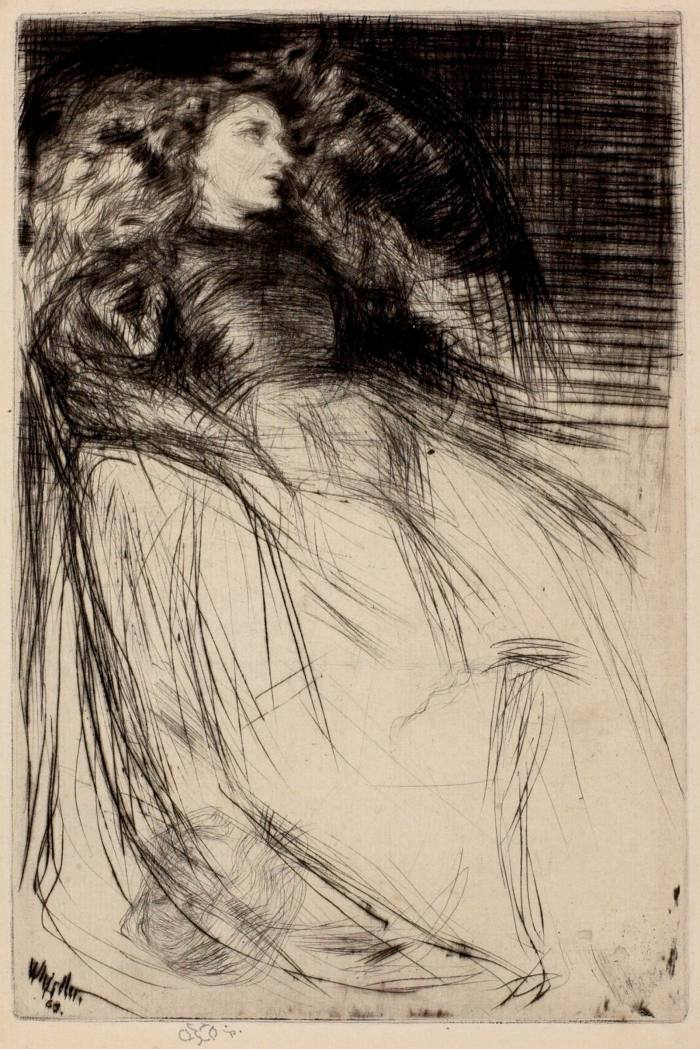

Although he described her as vivacious, Whistler sure liked her catatonic. Two gorgeous 1863 charcoals capture her sleeping, white features slack but her hair alive and buzzing like an electric halo. An etching of the same year, called “Weary”, once again fixes on her luminous locks, flaring in all directions.

Whistler’s friend Gustave Courbet painted portraits of Hiffernan over several years in the 1860s and he too hijacked her identity to make her look like different models who shared the same torrential tresses. Hiffernan admires herself in the mirror, but the face is fleshier, the eyes tinier, the neck thick and extended like a tortoise’s. The curators hoped to flesh out the individuality of the model, to un-erase her from history. And yet the show nearly accomplishes the opposite. She was 46 when she died in 1886. She lives on, less as a whole person than a set of fragmented projections.

If Hiffernan’s singularity dissipates in a welter of variations, elsewhere in the museum that approach becomes the whole point. The Double (to October 31) is half as interesting and twice as large as it should be. There are wonderful works among the cornucopia of twins, doppelgängers, double exposures, mirror images, shadows, reproductions, re-enactments, revisions and other forms of repetition — but you have to hunt for them. Ilse Bing’s trickily enigmatic “Self-Portrait with Leica” (1931), in which a pair of mirrors allows her to point the lens both at and away from us, stands out for being both doubled and unique.

The theme evolves into an obsessive assemblage, with artworks brought together for no better reason than that they involve multiples of two, or imitations of ideas that only ever worked once. Here’s a video of Alighiero Boetti from 1974, simultaneously writing the same phrase (“The body always speaks in silence”) forwards with his right hand and backwards with his left. Then, because no double should go undoubled, Mario Garcia Torres emulated Boetti’s ambidexterity three decades later and re-scrawled his own two-way missive (a 2006 headline from Kabul) on the walls of the National Gallery.

There’s a lot of that kind of gamesmanship in The Double. Bernard Piffaretti painted half of a canvas, then covered it and copied it on the blank half as best he could from memory. William Wegman offers two apparently identical self-portraits with his left hand shielding his face. Look closely and you still wouldn’t be able to divine the process: he moved the part in his hair from one side of his head to the other, strapped a wristwatch to the right wrist and used that hand to cover his face. Then he flipped the negative, performing a double reversal that gets the image nearly back to its starting point. Why, you might ask? To which the only appropriate response is an echo: why, indeed.

Follow @ftweekend on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

FTWeekend Festival, London

Save the date for Saturday, September 3, to listen to and more than 100 authors, scientists, politicians, chefs, artists and journalists at Kenwood House Gardens, London. Choose from 10 tents packed with ideas and inspiration and an array of perspectives, featuring everything from debates to tastings, performances and more. Book your pass at ft.com/ftwf

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here