It’s possible we’ve seen more of the moon and of Mars than we have of the oceans on Earth. Their depths are so vast, they’re impossible to simplify. It’s futile attempting to pile Eiffel towers or Everests one on the other to offer a sense of their scale. But as manned submersibles and remotely operated vehicles improve, we are seeing more of the worlds that they contain.

Everywhere one looks, species with new kinds of tentacles, light organs, lures, lipless mouths and sightless eyes are being found. New travel habits are being discovered. On an expedition to the unexplored depths of the Coral Sea Marine Park in Australia, researchers from the Schmidt Ocean Institute found a species of spikefish lurking. Until this sighting, the little creature had been thought of as a native of Hawaii, more than 6,800km away.

The first attempts by humans to explore the deeps were made more than 150 years ago. In the 1870s, Britain’s Challenger expedition conducted a landmark ocean survey that collected thousands of samples, discovered more than 4,000 new species, and explored the underwater world across 1.3 lakh km in four oceans (Atlantic, Southern, Indian and Pacific).

A century later, the US navy submersible Trieste descended to nearly 11,000 metres below the surface, into the Mariana Trench, in 1960.

Deep-sea submersibles are much sleeker and more manoeuvrable now, and a variety of them are being used to explore the deep seas. (In 2012, filmmaker James Cameron famously made a solo dive and sampled the bottom of the Mariana Trench.)

As a result, just since 2020, new records have been set for deepest-dwelling squid, octopus and possibly jellyfish. That last one was sighted at 10,000 metres below the surface (that’s nearly 1,200 metres deeper than Everest is tall). Here, the pressure is a crushing 1,000 times that on the surface. There is no light. Temperatures hover between 1 and 3 degrees Celsius.

Deeper questions

For ecologists, there’s an urgency to deep-ocean exploration. The pressing question is: How deep has the impact of the climate crisis gone? Changing temperatures are altering chemical compositions, life-cycles and ecosystems. Rising carbon-dioxide levels in these natural carbon sinks are altering gender balances and bleaching coral reefs.

“In addition, the ocean is heating up in its depths. Increasing ocean heat is probably the single most important Earth system metric for understanding human-caused global heating, but almost no one is aware of it,” says Peter Kalmus, a climate scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboartory, speaking on his own behalf. “This ocean heating is partly responsible for driving sea-level rise, as the water expands as it gets warmer.”

Further, Kalmus says, there’s extinction of marine life occurring under the ocean waters, and a mass migration of creatures toward the poles to adjust for heating waters, as well as a monumental change in ocean composition due to plastic.

“Even if we dropped to net-zero (carbon emissions) right now, the decline of oxygen in the deep ocean would carry on for a couple of centuries,” says Jon Copley, a deep-sea marine biologist with the University of Southampton.

This is because, for oxygen, the way to the bottom of the ocean is not straightforward. And even creatures living at extreme depths, unimaginable pressures and cold still need oxygen to survive. So how does it get there?

“A lot of it is carried by very deep ocean currents that form at the surface in polar regions and sink and spread from there. They take centuries to complete their cycle,” says Copley.

Those deep ocean currents are getting warmer as a result of climate change, and the amount of oxygen being carried by the currents is falling (keep in mind that CO2 levels are rising too).

This will intensify as emissions continue.

There’s also concern, as technology makes it easier to dive to greater depths. The seabed is now among the world’s richest reserves of valuable ores such as cobalt, nickel and manganese. Countries and mining companies are racing to secure the capability and the rights to dredge them out. This makes exploration missions more important and urgent, as it will provide baseline data before the onset of commercial activity in the depths.

“Now the focus is also about understanding the impacts of human activities in the deep sea,” says Copley, who is involved in one project in the eastern Pacific where a team of researchers is returning to a site where mining was simulated more than four decades ago, to see what how things have recovered, what life has returned.

“I think we may find that marine life has not completely returned to normal,” Copley says. “So what we need to find out is whether deep-sea ecosystems are particularly vulnerable (compared to ecosystems on land), and how impacts can be managed, for example with reserve areas that are not disturbed.”

.

TAKE A TOUR

A grassy sea monster

Indonesia’s Rafflesia arnoldii (aka stinky corpse) is the world’s largest flower and can grow to be 3 feet wide. The largest tree, the General Sherman giant sequoia, stands 83 metres tall and 11 metres in diameter.

But the world’s largest known living plant species is a seagrass called Posidonia australis, or Poseidon’s ribbon weed. It’s a single plant that’s about 4,500 years old, spread across an area of 112 sq km in Shark Bay (a Unesco World Heritage site).

It grew this big by repeatedly cloning itself. It is the most dramatic example of a naturally occurring clone. It is also being called the world’s largest living organism.

The shallow waters of Western Australia are home to seagrass meadows that cover up to 20,000 sq km. These marine meadows are home to a diverse mix of strains, containing 27 of the world’s 60 known species of seagrass.

Researchers at the University of Western Australia were studying this genetic diversity when they collected samples from what they thought were 10 seagrass meadows. What they found blew their minds: It was all one plant. Their findings were published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B in 2022.

.

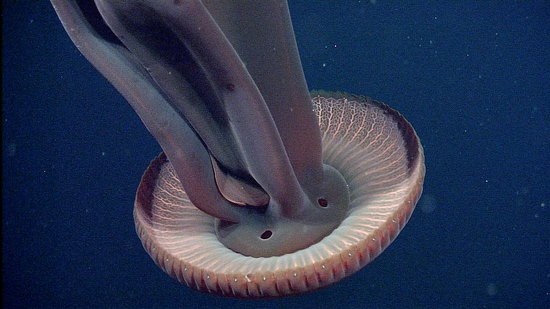

A ghost in the deeps

Jellyfish are as beautiful as they are deadly. The Stygiomedusa gigantean is also enormous. Dubbed the giant phantom jelly, sightings are rare. First discovered in 1899, it’s been spotted only about 100 times, at depths of up to 6,665 metres.

The velvety crimson deep-sea giant has a bell top more than one metre across and four ribbon-like tentacles, each up to 10 metres long, ending in a mouth (picture a very slim elephant trunk).

It is commonly found in the midnight zone, a region that stretches from 1,000m to 4,000m below the surface of the sea. It’s a place of perpetual darkness and, interestingly, the single largest habitat on earth, accounting for 70% of all ocean volumes.

The recent sighting of the giant phantom jelly in November 2021 — which resulted in rare, high-resolution images of it — was made by scientists from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) in California, at a depth of about 975m. This is the ninth spotting by MBARI, which has conducted thousands of deep-sea surveys with its remotely operated vehicle (ROV) named Doc Ricketts.

“Historically, scientists relied on trawl nets to study deep-sea animals. These nets can be effective for studying hardy animals… but jellies turn to gelatinous goo in trawl nets,” MBARI notes, in the video description of the sighting. “The cameras on MBARI’s ROVs have allowed MBARI researchers to study these animals intact in their natural environment… [capturing] stunning details about the animal’s appearance and behaviours.”

.

Blind, mean, lamp carrying fish

Across 2021-22, scientists from Australia’s Museums Victoria Research Institute spent 80 days mapping the seafloor of the Indian Ocean Territories, using a research vessel (RV) named Investigator. The vessel used underwater cameras, nets and sleds to sample habitats up to 5,500 metres below the ocean surface. It uncovered new, rare and strange-looking creatures, capturing high-resolution images and collecting samples for study.

• A previously unknown blind eel was collected from a depth of 5,000m. It has loose, transparent, gelatinous skin, and a mean jaw. Unusually for a fish, it gives birth to live young.

• Deep-sea batfishes (of the Ogcocephalidae family) with arm-like fins were found on the sea floor. What’s surprising about this species are its wide, earnest eyes and clearly demarcated nose and mouth, a most unusual look to encounter in the deep sea.

• The high-fin lizard fish, a deep-sea predator, was sampled. Photographs show its lipless mouth full of rows of small, spiky teeth on full display.

• Sloane’s viperfish, a harsh-faced creature with large, exposed fangs and rows of light organs on the underside, was sighted. It is among the oldest known deep-sea fish, first described in 1801. Its long upper fin has light organs on the tip too, to attract prey.

• A translucent flatfish (of the order Pleuronectiformes), was sampled. It has both eyes on one side of its head, to allow it to lie flat on the other side, camouflaged, on the sea floor.

.

A tulip, a squirrel, two arms on the move

In 2018, scientists from the UK’s Natural History Museum set out to survey the biodiversity of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific, using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). Specimens were collected and, for the first time, researchers could study the DNA of organisms living on the ocean floor.

The team collected 55 specimens across 48 species, 39 of which were found to be new to science.

“There were times when we did not see a single animal for quite a while. But incredibly, each animal we found was almost always a different species,” Guadalupe Bribiesca-Contreras, museum researcher and lead author of the study, says on the museum website.

Among the new species discovered was a sea cucumber nicknamed the gummy squirrel (it looks like a yellow chew toy) and an unidentified type of spindly Zoroaster starfish. Rare sightings included that of the translucent Peniagone vitrea, which looks like two attached arms on the move, and a Hyalonema, a foamy sea sponge that grows like a tulip. The findings were published in the journal ZooKeys in 2022.

This study was one of many undertaken in the region, an area of interest for seabed mining. It aims to help provide baseline information on biodiversity and evaluate the impacts of mining on this remote environment.

.

A professor, a student and a tree-climbing crab

What’s left of the mangroves in Kerala’s Kasaragod is considered critically vulnerable and still rich in biodiversity. New species are still being discovered here.

Researchers from the University of Kerala, for instance, found a new species of tree spider crab on a mangrove tree in 2019. It’s a surprising discovery because the crab is part of the Leptarma genus, and is the first of its kind ever found in India.

Riyas A, a researcher and student of aquatic biology at the university, was in a boat, collecting jellyfish blooms, when he first spotted the crabs. Squelching across the watery grove on foot, he decided to collect a few of the odd-looking creatures to take back to Suvarna Devi, a faculty member who specialises in crabs.

Devi noticed that the crab had an elongated ambulatory leg and an elongated propodus that put it in the Leptarma genus. When further digging confirmed that this was a previously unknown species, it was named Leptarma biju, after professor Biju Kumar, head of the department of aquatic biology and fisheries, who has discovered 50 species through his career.

“The extent of mangroves in Kerala has decreased from over 70,000 ha to around 4,000 ha due to indiscriminate destruction for coastal developmental activities and aquaculture,” Devi says. “This discovery reflects the highly biodiverse mangrove forests on Kerala coasts which needs special efforts for understanding and conservation.”

.

Finned squid, a Dumbo octopus, a jelly-like blob

In 2021, researchers went looking for a World War 2 naval destroyer in the Philippine Trench. They were in a manned submersible piloted by Victor Vescovo, founder of the private ocean-exploration company Caladan Oceanic, and its chief scientist Alan Jamieson, a deep-sea researcher from the University of Western Australia. At 6,200 metres, they found the wreck, and while they were at it, also spotted the deepest-dwelling squid known so far.

The Magnapinnid, of a group commonly called the big-fin squid, has been visually recorded only a dozen times since 1988. In footage from the excursion, it can be seen as a hazy shadow, illuminated by the submersible’s piercing light. The squid has a large, wavy fin protruding from one side and eight long, spindly arms that dangle and flow from the other.

Jamieson and Michael Vecchione, a zoologist with the Smithsonian Institution, published their findings in the journal Marine Biology in 2021.

In 2020, the two also discovered a new deepest-dwelling octopus, a species of Dumbo octopus spotted at 6,957 metres, in the Java Trench. (The previous record was 5,145 m.)

In 2021, the team found a jellyfish-like blob at a crushing depth of 10,000 metres, which is yet to be described. If it does turn out to be a jellyfish, Jamieson will be three for three on finding and describing the deepest-living octopus, squid and jellyfish.

.

The way of water

It’s like a scene out of Avatar 2. At a depth of 1,600 metres, at the Coral Sea Marine Park in Australia, a research vessel has captured imagery of stunningly detailed corals, brightly coloured sea-dwellers, glowing jellyfish, and a seafloor sprinkled with what look like precious stones (they’re actually corals).

All the footage was captured remotely, during the pandemic-induced lockdowns of 2020, as the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s research vessel Falkor spent 46 days mapping less-explored deep-sea reef systems at the marine park.

Scientists found 30 large coral banks, submarine canyons, stretches of dunes and remains of landslides. In all, the operation collected over 91 hours of video footage from across 35,000 sq km, making this one of the best-explored marine regions around Australia. (A lot of the footage is available on the institute’s YouTube channel, Schmidt Ocean.)

The team also identified up to 10 new species of fish, snails, sponges, deep-water sharks and nautiluses. One of the surprises was a species of spikefish known to be native to Hawaii. Finding it near Australia significantly increases its known range.

.

Upside-down waterfalls

In 2021, a group of scientists from US and Mexico found new hydrothermal vents in the Gulf of Mexico and possible new species living around them. A 33-day expedition aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s research vessel Falkor used its remotely operated vehicle SuBastian to explore vents emitting fluids at temperatures of up to 287 degrees Celsius.

SuBastian captured images and footage of hydrothermal mirror pools, calcite spires (which look like stalagmites), iridescent blue-scale worms, and other unique animal communities thriving in this extreme environment. In the absence of light, animals here use chemosynthesis, as opposed to photosynthesis, to live.

The possible new species include types of arrow worms, crustaceans, molluscs and roundworms. “There appear to be differences in which vent animals dominate these different hydrothermal features,” co-principal investigator Victoria Orphan says on the institute’s website. “The sites to the south had the highest density of blue scale worms, while others appeared to be more densely colonized by chemosynthetic anemones or tube worms.”

The hydrothermal vents are also unique in appearance, possibly owing to the chemical composition of the waters around them. Unlike most others, these emit clearer fluids, giving them the appearance of upside-down waterfalls.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here