India’s largest flower is the Sapria himalayana or hermit’s spittoon. It has a diameter of about 20 cm, and has large, bright red petals covered in sulphur-yellow dots. It can be found in the wild only very rarely in India, and the best bet of ever seeing it is in the digitised archives of the Botanical Survey of India (BSI), now open to the public at archive.bsi.gov.in.

In the archives are a total of 5,800 life-sized paintings of Indian plants, created in the 1700s and 1800s, reflecting a history of passionate data-gathering and artistry.

There are paintings of rare plants, common plants, as well as a section of specimens dried and preserved on paper, all of which took the BSI over 10 years to digitise.

“All the botanical portraits were made using natural vegetable dyes, during the time of the British East India Company,” says BSI director AA Mao.

When the British surgeon and botanist William Griffith first named and catalogued the Sapria himalayana for the Western world in 1844, for instance, having sought it out in Arunachal Pradesh, the camera was still in its infancy and camera film hadn’t yet been invented. But two years earlier, the flower was documented as art, in a painting created by an artist named Lutchman Singh near Kolkata.

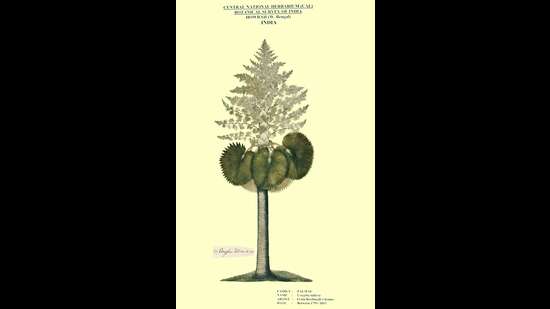

Other paintings in the BSI archive depict plants so unfamiliar and now-long-extinct that they evoke the sense of wonder with which they were clearly created. One such is the Corypha taliera, a native of Myanmar and of India’s Bengal region, with features that make it look like a cross between a palm tree, an oak and a fir. It was documented by Scottish surgeon and botanist William Roxburgh and painted between 1793 and 1813. “The painting is now the only evidence of the Corypha taliera in the wild,” says K Avinash Bharati, BSI botanist and custodian of the digital archive.

Paintings commissioned by Roxburgh make up a large part of the archive. Between 1780 and 1815, he commissioned 2,532 works. These are now known as the Roxburgh drawings, in part because he did not document any of the Indian artists’ names.

“All we know is that these drawings were made by Mughal-era painters for a fee of a few rupees per painting,” says Bharati. “This archive, in a way, is a tribute to those artists,” adds Mao.

Plants on paper

Paintings were by far the easiest means of preserving a record of natural history specimens. They were easy to store and transmit. Most importantly, since India was hot and humid, paintings could be stored far more safely than the specimens themselves. “They served as a durable medium,” says Bharati.

The paintings were generally life-size and were painted in the field, in the plants’ natural settings, to ensure accuracy. This means the unnamed artists would have sometimes had to undertake arduous treks in order to reach them too.

“Roxburgh commissioned coloured drawings comprising twigs of plants with upper and lower surfaces of leaves and dissected flowers and fruits as well, to show internal characters of the plant,” Bharati says.

In the course of field explorations, samples of plants were also collected in the reproductive stage to make a herbarium — a collection of dried and pressed plant samples mounted on hard paper. Among these collections, sometimes some samples turned out to be unknown to science. These were categorised by the botanists as a new species, and the specimens were called type specimens, because they would now serve as authentic reference material for that new species.

In its online archive, BSI has painstakingly digitised these herbarium specimens too — all 28,000 of them, from a total of 87 territories around the world.

“British researchers from BSI headquarters in Kolkata travelled the world in the 1700s and 1800s and collected plants and deposited them here,” says Bharati. “A majority of the foreign type specimens are from then-British colonies such as Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. There are about 5,000 from Malaysia alone.”

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Art-Culture News Click Here