It is 8 a.m., and as Michael Bublé’s rich baritone reminds me that it is beginning to look a lot like Christmas, my kitchen fills with the warm, gently-spiced aroma of masala oats. A spicy carb is my favourite way to kickstart the day, and the version in Farokh Talati’s Parsi – From Persia to Bombay: Recipes & Tales from the Ancient Culture is the recipe of choice this morning.

Chef Farokh Talati

| Photo Credit:

Bloomsbury

It is simple enough — a few vegetables, finely chopped, dotting the spiced oats like confetti — and comes together in 10 minutes, which is my main requirement for a weekday breakfast. But the asafoetida in the oats takes me by surprise, as asafoetida often does, and I get that warm fuzzy feeling of finding a recipe that I know I’m going to make again.

Talati’s book has been garnering a lot of attention since it came out in November. Beautifully produced, ‘it gathers together a selection of classic Parsi recipes from his travels through India and time spent in the kitchen with family’. Talati is the head chef at London’s St. John Bread and Wine, and ran a popular Parsi supper Club in the city until 2020.

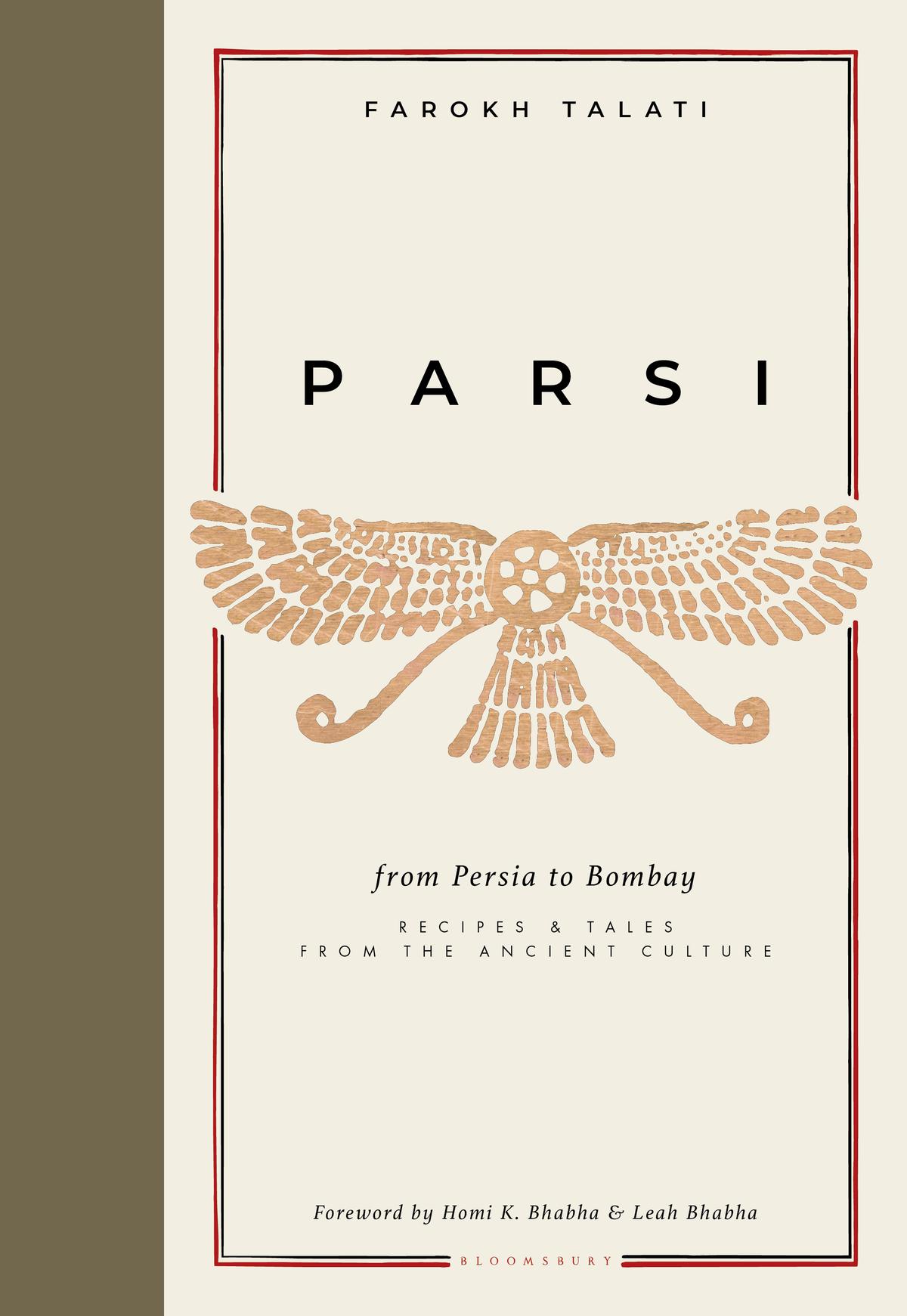

Parsi – From Persia to Bombay: Recipes & Tales from the Ancient Culture.

| Photo Credit:

Bloomsbury

In many ways, Parsi reminds me of Dishoom by Shamil Thakrar, Kavi Thakrar and Naved Nasir, and Jerusalem by Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi. All three books, written by London-based chefs, are love letters to their home cities — Jerusalem to, well, Jerusalem, and Dishoom and Parsi to Mumbai (and parts of Gujarat to some extent, in the latter). Like these other books, the photos in Parsi are also a mix of crowded streets, chaotic markets where life and the world are spilling out of the frames, juxtaposed with clean, tightly constructed forms where the magic from these markets is distilled and transformed into impeccably-styled food against minimal backdrops.

Coconut and some improvisation

There is a fine line between an aspirational yet approachable cookbook, and one that is intimidating. While the visual language is chic and minimal, the writing in Parsi is warm and approachable.

Dishes and drinks featured in Parsi – From Persia to Bombay: Recipes & Tales from the Ancient Culture.

| Photo Credit:

Bloomsbury

Talati is a chef with a keen understanding of home cooking, and the constraints of a home kitchen. He encourages you to use up those old spices at the back of the cupboard: ‘there is no instance where your whole spices have been out that long that you have to throw them away.’ ‘Remember, there is no right or wrong, only deliciousness,’ he writes about improvisation. It is, ultimately, a book that invites you to use the recipes as a map to discover new landscapes within your own kitchen.

The season’s festivities have meant that about 80% of my diet in the last week has been copious amounts of butter and flour. There has not been a vegetable in sight for days. Looking through Parsi, I find a recipe for Pumpkin and Coconut Curry. Pumpkin and coconut — coconut milk, desiccated coconut and coconut butter — gently simmered in a heady, roasted coriander-cumin spice blend. Reassured by Talati’s insistence to improvise when needed, I swap the desiccated coconut for freshly grated coconut, and leave out the coconut butter entirely. The resulting dish, that I spoon over steamed rice, is sweet and sour and wholly comforting.

Chef Farokh Talati taking notes at Café Colony, a 90-year-old Parsi restaurant in Dadar.

| Photo Credit:

Bloomsbury

The larger community story

This is a book I am excited to cook from, and while flipping through, I see many that could potentially be added to my small but growing recipe repertoire — a tamarind and fish curry for a weekend for when we have family visiting, a roasted kid shank and brown lentil for when we need the heavy-duty comfort of a slow cooked meal, and a raspberry and rose ice cream for a warm summer afternoon.

But, for a cookbook that Talati hopes will ‘become a book that can be picked up in many years to come, and represent a slice of our culture and heritage,’ I find it lacking in certain ways. As much as it aims to provide insight into the Parsi community — and many of its recipes certainly do — it lacks a few elements that could have made this great cookbook a classic. The recipe introductions provide a little, but nowhere near enough, context. For example, it remains unclear why there is a recipe for Knickerbocker Glory in the book. How does it tie back to the larger Parsi story that the book is telling?

Dinaz aunty making tamarind and coconut fish curry. “She follows the recipes and techniques handed down to her from her mother with the utmost rigour,” says Farokh Talati; and Maneck aunty (left) and Nergish aunty.

| Photo Credit:

Bloomsbury

I am not suggesting that cuisines are static, and impervious to evolving, but several recipe introductions are disconnected and fail to tell a cohesive story. There is a recipe for Quince and Rose Paste that sits between Salted Mango Pickle and Beetroot and Mustard Seed Chutney. Talati talks about learning to cook with quinces in his (I’m presuming restaurant) kitchen in the introduction to the recipe. But Google also tells me that quince, or ‘ beh’ as it is called in Farsi, is a fruit that is much beloved Persian ingredient. There is sadly, a missed opportunity to dig deeper and tell a better researched story with Parsi.

It also seems a fairly significant oversight that a book that hopes to become a Parsi classic does not mention that this book is written by a Parsi brought up in the West, writing primarily for a western audience.

But for now, it’s a cold rainy Friday night in Bengaluru. The sun has been hiding behind thick, grey clouds for days now, but I find a recipe in Parsi for just this sort of evening. A slow-cooked lamb stew, studded with sunshine-coloured dried apricots, and whole spices for warmth. The pieces of lamb are first browned, followed by an onion. Aromatics, apricots, potatoes, water and a long, slow cook. By the time it’s ready to eat, the windows have fogged up, and the cat is pacing the kitchen, followed by the humans in the household, lured by the intoxicating smell of slow-cooked meat. Deeply savoury, with pockets of sweetness, we add a few chopped fresh green chillies for heat. Jamva chalo ji, let’s eat.

The writer is editor and co-founder of The Goya Journal.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Food and Drinks News Click Here