This article is part of FT Globetrotter’s new guide to tennis

It was the bored monks of medieval France who invented the sport that has become one of the most captivating of modern times. To pass the time, they struck a ball against a wall, and then over a crude net, using nothing but their bare hands. Overindulgence in the improvised jeu de paume, “game of the palm”, led to painful bruises and callouses, so they began to use gloves. Some of them sought a technological edge by sewing webbing between the fingers. The game grew in popularity.

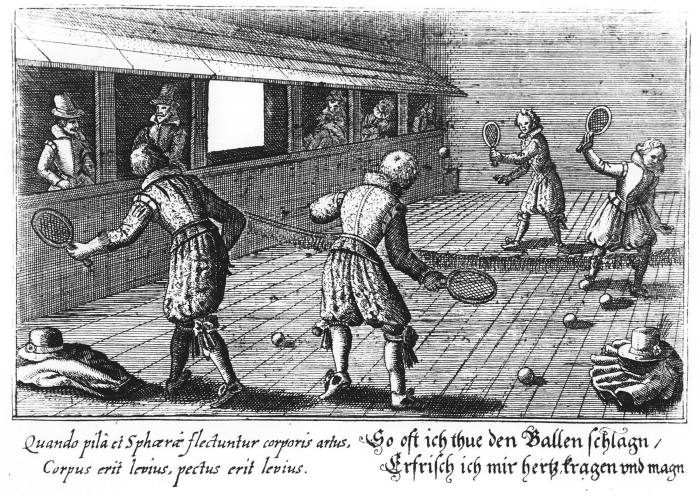

By the beginning of the 16th century, players were using small paddles or primitive rackets (from the Arabic rakhat), strung with all manner of substances, to be able to hit the ball with more power. And now the game of tenez, or tennis, had escaped its monastic confines and caught on with the royalty of Europe. The rackets became more sophisticated, shaped asymmetrically to counter the ball’s low bounce off the floor.

The game, what we know today as real tennis, began to lose its appeal over the following centuries, but was supplanted by a new form of the sport, which could be played outdoors. New game, new tools: it was Major Walter Clopton Wingfield who designed the first lawn tennis racket in 1874, packaged for sale in pairs, complete with net and balls, in one of sport’s first and canniest marketing exercises. The following year, across the channel, Pierre Babolat produced the first natural gut strings for the new design, and two years after that came the founding of the Wimbledon tournament. Modern tennis was up and running.

Following that decade’s flurry of activity however, tennis did not change much, and nor did its equipment. Rackets were made of solid wood, making them heavy and difficult to manoeuvre: think of that the next time you see those slightly ridiculous players’ movements in early footage of the game. But in the mid 20th century, technology was ready to make another leap forward, with the development of laminated rackets.

The use of layers of wood, glued together, made rackets lighter without any sacrifice of power. Tennis technique evolved correspondingly: suddenly it was possible to apply greater spin on the ball, turning rallies into something that looked like chess. This was the beautiful game I grew up with, power and elegance perfectly poised.

I bought a Dunlop Maxply Fort in my first year at university in the mid 1970s, and was solemnly told I needed gut strings rather than the new, widely promoted, synthetic types, because it would give me greater “feel”. I agreed, of course. It was the era of the first Star Wars film, and like the young Skywalker, I instantly ascribed metaphysical powers to my new weapon, taking care to wield it with a properly soulful respect for its properties.

But racket manufacturers had more prosaic thoughts: they wanted more power in their product. In 1967, the Americans Clark Graebner and Billie Jean King appeared in the US National Championships wielding a new type of racket, the Wilson T2000, which was made of steel. “Like a feather,” said King, on her way to the title. “An oversized tea-strainer,” mocked Time magazine.

But this was a revolution; wooden rackets were on their way out. A brash American, Jimmy Connors, made the T2000 famous. And the following decade saw yet another advance: the appearance of the Prince Classic, the first oversized racket, used by a small amount of professionals but soon to be loved by many, many enthusiastic amateurs, for its enlarged “sweet spot”.

As in other spheres, the 1970s was a wild time for tennis rackets. At the beginning of the decade, a German horticulturalist, Werner Fischer, invented the “spaghetti” racket, using a bizarre string configuration that imparted massive spin on the ball. It was regarded as a joke, until the mischievous Ilie Nastase used one against the Argentine clay-court master Guillermo Vilas, unbeaten in 53 games on his favourite surface. Nastase took a two sets to love lead, before Vilas walked off in protest, “completely disconcerted and discouraged” by the trajectory of the ball. The spaghetti racket was banned.

Experiments continued on finding the perfect combination of power, flexibility and, yes, feel. The 1980s saw the first graphite rackets come on the market and we suddenly had the greatest game-changer since Wingfield. Universally adopted by all players, here was a winning racket, for club players and Grand Slam champions alike. Since then, rackets have been much of a muchness, using different additional materials such as boron, Kevlar, titanium and tungsten, in greater or lesser proportions.

The super-rackets made the game look easy; too easy. In 2003 a group of the world’s leading tennis names — John McEnroe, Boris Becker and Martina Navratilova among them — wrote to the International Tennis Federation calling for a return to smaller rackets, to prevent the game becoming “unbalanced and one-dimensional”.

Their plea was given short shrift. Just as well: tennis in the age of the Big Three who have dominated the men’s game, Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic, is as absorbing a spectacle as it has ever been.

And today’s rackets? They are sleek, light, and friendly, forgiving of many a mis-hit thanks to their benign technological innovations. Those that require greater control even come with a warning: “This is NOT a racket for beginners” — of course, there is no greater come-on for beginners who dream above their station. We are urged to buy Federer’s brand of racket (Wilson) or Nadal’s (Babolat), although in truth the top players tend to have idiosyncratic requirements that bear little resemblance to what can be found on the high street.

In fact, the most interesting thing to be observed about rackets today is the wide variety of ways in which they are destroyed by the temperamental outbursts of impassioned players. Look out for the Frenchman Benoît Paire, who once told an umpire who penalised him for pulverising his racket on the ground that it was fine because it was “already broken”; and Nick Kyrgios, who to avoid a penalty once took two rackets off court and into a hallway, smashed them and returned to the court with their broken remains.

The next phase in the evolution of the racket: indestructible. Now that would be boring.

Do you have a favourite tennis racket? Tell us in the comments

Follow FT Globetrotter on Instagram at @FTGlobetrotter

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Travel News Click Here